By Philip Sean Curran, Staff Writer

A Princeton University professor shared the Nobel Prize in physics with two other academics for their theoretical discoveries into matter, it was announced Tuesday.

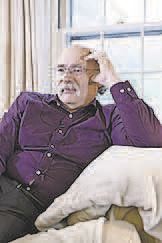

F. Duncan Haldane, a Princeton professor since 1990, came to work as usual to teach a morning class, hours after getting the news during a 4:30 a.m. phone call that he had won. Later in the day, at a news conference at on campus, Mr. Haldane touched on his work, explained how most discoveries are “accidental in some way” and offered credit to an early mentor in his career.

“You don’t get up at the beginning of the day and say, ‘I’m going to discover something great today.’ You’re doing whatever you’re doing and you happen to chance on something through some other route,” said Mr. Haldane, 65, who is originally from London. “And you have to have, of course, the insight to see that what you’ve found is something interesting and worth exploring more.”

He pointed to the influence of his former adviser, Philip Anderson, a Nobel Prize-winning physics professor who taught at Cambridge University, where Mr. Haldane earned his undergraduate and doctoral degrees. Mr. Anderson, who also taught at Princeton was in attendance for the news conference.

Mr. Haldane shared this year’s award with David J. Thouless, a retired professor at the University of Washington, and J. Michael Kosterlitz, a professor at Brown University.

“This year’s laureates opened the door on an unknown world where matter can assume strange states. They have used advanced mathematical methods to study unusual phases, or states, of matter, such as superconductors, superfluids or thin magnetic films,” according to a news release issued by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the organization that awards the prize.

The three men will split the $1.2 million prize money, with Mr. Thouless getting half and Mr. Kosterlitz and Mr. Haldane dividing the rest, the Academy said.

“I think my life’s work was validated whether or not I got such a prize,” Mr. Haldane said. “I was very happy that I’d actually been fortunate enough to be able to make such contributions to this field. I don’t think one needs a prize to validate my work and one doesn’t spend the time worrying about if you’re going to get a prize.”

Earlier in the day, Mr. Haldane’s graduate students clapped for him at class that morning. At Princeton, he is known to colleagues as funny and light-hearted, yet focused on his work.

“I believe we’re all quite excited about it,” said physics professor Zahid Hasan of Mr. Haldane getting the Nobel.

“If you find Duncan, you find him typically with a piece of paper or blackboard. He’s brilliant, and he works extremely hard,” added fellow professor Shivaji Sondhi.

Princeton President Christopher L. Eisgruber recalled at the press conference that he had earned his degree at Princeton in physics. He jokingly described himself as “utterly unqualified to explain Professor Haldane’s work.”

“His work has important implications for the understanding of new types of materials, with the potential to influence future generations of electronics, superconductors and quantum computers,” Mr. Eisgruber said.

This is the second year in a row that a Princeton professor has won a Nobel; last year, economist Angus Deaton claimed the prize in economics.

“In a department of unusually creative people, Duncan stands out,” said physics department chairman Lyman A. Page during the press conference. “In the broader theoretical community of physicists, he is known for his extraordinarily deep insights and mathematical elegance.”