By JENNIFER AMATO

Staff Writer

NORTH BRUNSWICK — To commemorate Veterans Day, interns at Elmwood Cemetery in North Brunswick led historical walking tours designed to share the area’s extensive history while acknowledging the contributions of those who have served the country.

The first stop on the World War I tour on Nov. 11 was at the gravesite of Ella Kearney, a nurse who was in charge of shell-shock cases. World War I saw the beginnings of the Red Cross, and the number of nurses involved in the war grew from 480 to 20,000, according to information read by Elmwood intern Philip Ripperger.

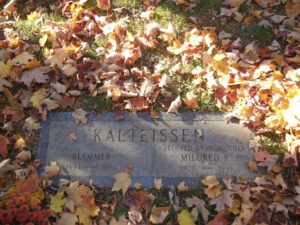

Next, Klemmer Kalteissen was drafted into the war. He graduated from law school and eventually opened an office on Paterson Street in New Brunswick. He served as a deputy surrogate, freeholder director and presiding judge in Middlesex County. He was also part of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and was on the board of Saint Peter’s University Hospital. In addition, he served on boards of education in North Brunswick, South Brunswick, East Brunswick and Princeton. Ripperger said Kalteissen lived a successful life after the war, dying on April 20, 1984, at age 89.

Nurse Sally Macaulay Parker was from the well-known Parker family. Her mother, Henrietta Parker, financed a fleet of ambulances for Sally to drive in France. Because 30 percent of deaths during World War I were gas-related, Ripperger said, nurses and doctors had limited experience, while also facing amputations due to infections because antibiotics did not exist.

After the war, Sally lived in France as a nurse.

Henrietta later established Parker Home because her husband did not have round-the-clock nursing care before he died, according to Kearney Kuhlthau, historian and genealogy researcher for Elmwood.

The fourth gravesite belonged to Dr. Ernest T. Dewald. He was born in New Brunswick in 1891, received his bachelor’s degree from Rutgers University, earned his master’s degree and doctorate from Princeton University, and became a linguist, having learned eight languages. He was also a professional singer.

During World War I, Dewald was sent on special intelligence gathering missions, Ripperger said, since the CIA was a new concept.

“Especially with the global war, it was much more necessary to share information with other countries that were working together in the war,” the Rutgers University student said.

After the war, Dewald taught at Rutgers and Princeton.

He was also sent to reclaim stolen art from the Nazis after World War II — one of the esteemed “Monument Men.” He then ran the Princeton University Art Museum.

The next resting place visited was for Elizabeth B. Dalrymple, a 26-year-old graduate of New Brunswick High School and the New Jersey State Normal School at the time of the war. She did her training at Walter Reed Army Medical Center and served at Fort Dix.

Ripperger said nurses were not recognized as wartime servicewomen at the time, though they did eventually receive credit later on.

“At a time when women couldn’t vote, [it was] incredible they were doing so much to serve their country,” he said.

Herbert Nafey was also a New Brunswick native, who received his degree from Rutgers and his doctorate from the University of Pennsylvania. He was an intern at New York Presbyterian Hospital.

In 1917 at 30 years old, Nafey entered World War I, serving as a lieutenant in the military medical corps, Ripperger said.

Upon his return to the United States, he joined the Highland Park Military Reserves, and in 1946 was appointed president of the New Jersey Society of Surgeons. He died in 1951 at age 64.

Harry Richardson was a New Brunswick High School and Rutgers University graduate who served in the 78th Infantry Division and fought against the Germans in France. Less than 50 days after he joined the military in 1918, he was thrust into the Battle of the Argonne Forest, considered one of the greatest American achievements during the war, Ripperger said, which led to the Armistice in 1919.

Once home, Richardson founded Richardson Engineering Corps in New Brunswick, served on the Board of Education and with the New Brunswick Parking Authority and dedicated his time to many civic and charitable organizations.

Ripperger then pointed out an area of single plots of adult veterans. Four of note belong to natives of Crete and Greece who came to the U.S. to escape the Balkan Wars in Europe, but who then found themselves back in Europe fighting for America. He said all four were drafted in 1917, trained at Fort Lewis in Washington state, traveled from California to New York, arrived in France in cattle cars and then found themselves on the front lines.

One of the most prominent sites at Elmwood belongs to the Johnson family, a mausoleum that houses Robert Wood Johnson, James W. Johnson, Roberta Johnson and Robert Wood Johnson Jr. The Greek temple-styled granite building with pink marble inside was built in 1911 and is still maintained by Elmwood staff, Ripperger said.

The family founded Johnson & Johnson in 1886. They then contributed heavily to World War I, with the foundation raising $400,000 (valued at $10 million today) in two years by selling bonds and hosting a dinner with President William Howard Taft that raised $17,000.

Ripperger said, essentially, every resident of New Brunswick had contributed $100 to the war effort at the time. He also said that of the 35,000 city residents at the time, 30,000 were estimated to attend a parade for the soldiers, not including the people actually participating in the parade.

The Wright-Martin Aircraft Corporation was also located in New Brunswick at the time.

Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital was founded in 1884 as New Brunswick City Hospital, but was renamed in 1986 after Robert Wood Johnson Jr.

The last stop on the tour was at the family plot of Joyce Kilmer, the famous poet who wrote the poem “Trees” based on an oak tree on the Rutgers campus. Kilmer was a member of The Daily Targum newspaper at Rutgers and was part of the staff of the New York Times in 1913.

Kilmer enlisted three weeks after the war started and was a regimental historian. He was killed by a sniper in 1918 and was buried in France, receiving the French equivalent of a medal of honor.

Joyce’s father Frederick was a scientist for Johnson & Johnson and built the Hill House, which was knocked down to build Brower Commons on College Avenue in New Brunswick. Joyce’s family is buried at Elmwood, accompanied by a monument in Joyce’s honor.

Camp Kilmer and the Kilmer Post Office in Edison, as well as Joyce Kilmer Avenue in New Brunswick, bear his namesake.

Elmwood Cemetery is a Victorian garden cemetery founded in 1868. The founders designed a cemetery where a beautiful landscaped park would create a respite from expanding cities, according to Eleanor Molloy of the Elmwood Cemetery Association. Because of their vision, Elmwood is a preserve of 50 acres of native trees and shrubs and home to many birds and wildlife.

The cemetery’s garden has been certified as a Monarch Waystation and a North American butterfly garden and was created to provide milkweeds and nectar sources for butterflies native to New Jersey, particularly the monarch butterfly, Molloy said.

In addition, Elmwood opened its grounds to the public for a luminaria on Nov. 6, lighting more than 3,000 candles on site.

For more information on special events at Elmwood, visit www.TheElmwoodCemetery.com/events, call 732-545-1445 or email [email protected].

Contact Jennifer Amato at [email protected].