By Philip Sean Curran, Staff Writer

When Fidel Castro arrived at Princeton University in April 1959, he was greeted like a rock star.

“The mob surged past two cars blocking their way and were kept from Castro only by the strong-arm tactics of the police. At least two undergraduates were thrown bodily back into the crowd,” the college newspaper, the Daily Princetonian, reported at the time. “Although the mob was almost completely out of control, there were no signs of unfriendliness toward Castro.”

“It was a big deal,” said Princeton graduate Jay Siegel, a senior in 1959. People, he recalled, viewed Mr. Castro as the “champion of the common man.”

“Students were quite enthusiastic about what he represented,” said former U.S. ambassador Paul Taylor, a Princeton undergraduate at the time.

Mr. Castro died Nov.25, at 90. Yet when he arrived in Princeton, he was at the very beginning of his power. Mr. Taylor, a 1960 Princeton graduate, was there for Mr. Castro’s Princeton visit, part of a tour of the United States that the new prime minister – later president – of Cuba was making.

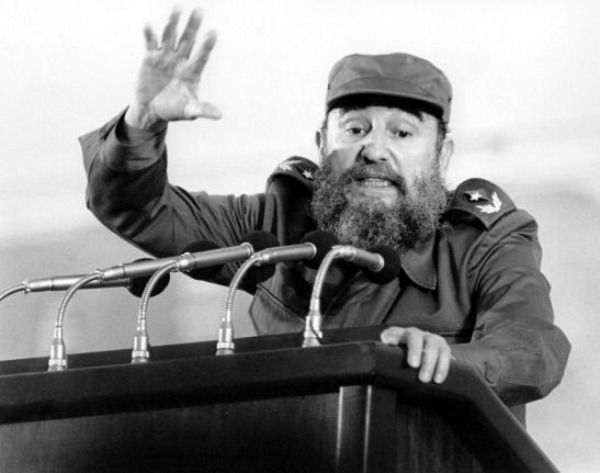

Mr. Castro, then only 32, spoke at the Woodrow Wilson School on April 20, a Monday. Mr. Taylor was in the audience that night listening and taking notes that he later typed up, kept for decades and later donated along with other Castro-related items to the Mudd Library, home of the university archives.

Mr. Castro, who did not identify himself as a communist at that point, spoke of striking a middle ground between communism and capitalism, Mr. Taylor recalled. His notes of Mr. Castro’s speech included the following:

“We must satisfy material needs and serve other purposes. But to satisfy men’s material needs, we are satisfying men’s material needs without sacrificing freedoms. That is what we are doing, without dictatorships.”

Later, in response to a question from the audience, Mr. Castro said: “I advise you not to worry about communism in Cuba. When our goals are won, communism will be dead.”

Mr. Castro would rule Cuba as a dictator for roughly half a century — as a communist.

Fred Hitz, a 1961 Princeton graduate who later worked for the CIA, remembered Mr. Castro arriving in a long parade of limousines and being surrounded by mufti-clad soldiers in dark green. Mr. Hitz was an assistant to then-history professor Robert Palmer, who served as the official host for Mr. Castro’s visit to the Woodrow Wilson School. Mr. Palmer, he recalled, introduced Mr. Castro, who then took center stage.

“And he spoke. And he spoke. And he spoke,” Mr. Hitz said with a touch of humor about Mr. Castro’s lecture.

After a while, Mr. Hitz said, the professor realized that this would not be the exchange of views that the event was supposed to be.

“Needless to say, it was a one-sided oration,” Mr. Hitz said.

He recalled how Mr. Palmer even went so far as to go up to Mr. Castro at the podium to tell him his time was up.

There was extensive media coverage of the trip, with a photo appearing in the Daily Prince of Mr. Castro standing on Washington Road amid a throng of people, including men in fedoras, a sign of the times.

Mr. Castro later went to a reception at Morven hosted by Gov. Robert B. Meyner, then stayed overnight in Princeton to speak at the Lawrenceville School the following day before leaving by train for New York.

So how did Mr. Castro get to Princeton? As a Princeton undergrad, Mr. Taylor had written in March 1959 to Mr. Castro inviting him to come to campus. A copy of his letter, which he donated to Mudd, read in part: “I am sure that your visit here would do much to help students here in the United States understand the real meaning of the Cuban Revolution, which you inspired and now lead.”

He turned down the request but came in response to a faculty invitation, Mr. Taylor recalled.

A university alumnus and Rutgers professor, Roland Ely, helped make the Castro appearance happen, according to an article in the Princeton Alumni Weekly, in April 2009, on the 50th anniversary of the visit.

The article stated that Mr. Ely lived in town and was a “sympathetic cousin of a Castro insider.”