Hank Kalethttps://plus.google.com/[email protected]

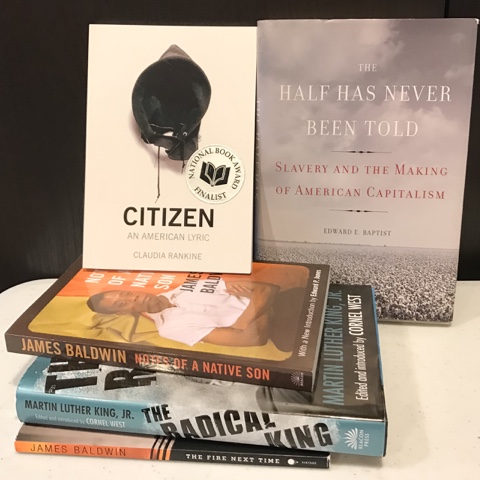

, The short essay that follows was inspired by the announcement that the indispensable podcast “Our National Conversation About Conversations About Race” was ending its two-year run. If you haven’t listened, go to its archives and dive in., Americans have a problem when it comes to race. This is not news. It’s baked into our history. It undergirds our attitudes, our language, our voting patterns. It structures our economy, delineates our neighborhoods, our views of crime and punishment., It’s there, both front and center and in the background, and until we admit this nothing is going to change., I know what some of you — meaning my readers, friends from my younger days, my critics — will say: “I am colorblind,” you’ll tell yourself. “It’s about character, experience, knowledge.” “I don’t see race,” you’ll say as you cross to the other side of the street, as you become watchful of the black kids in the mall, as you nod at the race joke and laugh., I’m not calling anyone a racist. I can’t be in the head or heart of anyone but myself. And I’m not saying my hands are clean — I admit I need to check the impact of this history on my own subconscious actions and prejudices., Under the Christian doctrine of original sin, , at least as I understand it (being an agnostic Jewish existentialist and not a Christian), we cannot escape this taint. All we can do is repent and ask forgiveness. Slavery is America’s original sin, and I — all of us, really — can’t help but be tainted by it., American racism was both created by, and helped create the so-called “peculiar institution” of slavery. It helped justify the violence used to control slaves and created the racial hierarchy that distorted the allegiances of poor whites, made them complicit in an evil from which they derived little and that was used to erase racial and caste resentments., This is where white privilege begins — with the notion that skin color is destiny. Privilege, in this context, does not imply special benefits in the way we normally view them. Poor whites are still poor, and middle class folks like myself still have to pay our taxes and shovel the walk ways when it snows. Rather, it implies a kind of immunity — getting pulled over by police does not lead to an existential crisis, for instance, and the kinds of slights (“micro-aggressions) that African Americans are expected to live with do not happen to us. (I should say “most of us” — as a Jew I live with a different set of “micro-aggressions,” but that is a different essay.), Claudia Rankine’s book Citizen, uses these slights (does this word minimize the impact?) in an effort to show how the seemingly small, inconsequential moments are part of the larger web of privilege and racism. As, The New York Times wrote, when the book came out:,

“Citizen” begins quietly, with descriptions of how encounters between people of different races can turn hurtful or puzzling or disconcerting in the space of a few words. The stories come from her own life and from people in her personal and professional circles.

One cannot forget the times a friend called her by the name of a black housekeeper. Another suffers a lunch companion who complains that because of affirmative action, her son cannot attend the same school that she, her father, her grandfather “and you” all attended. Yet another shows up for her appointment at the house of a specialist in trauma therapy. The therapist opens the door and yells: “Get away from my house! What are you doing in my yard?”

Ms. Rankine said that “part of documenting the micro-aggressions is to understand where the bigger, scandalous aggressions come from.” So much racism is unconscious and springs from imagined fears, she said. “It has to do with who gets pulled over, who gets locked up. You have to look not directly, but indirectly.”

, There is a continuum connecting privilege and micro-aggressions to white supremacy and Dylan Roof-level violence. Roof, the white man who killed nine African American churchgoers in South Carolina two years ago, occupies a distinct position on this plane, along with Bull Connors and Jim Clark, but that does not absolve the rest of us of our guilt., We are complicit, remain complicit, and cannot claim redemption until we first admit our sin and seek forgiveness by engaging in the debates and fighting to alter a system that was built on sin and maintains its power by playing on the worst instincts of the broader American public., Send me an e-mail.,