By Philip Sean Curran, Staff Writer

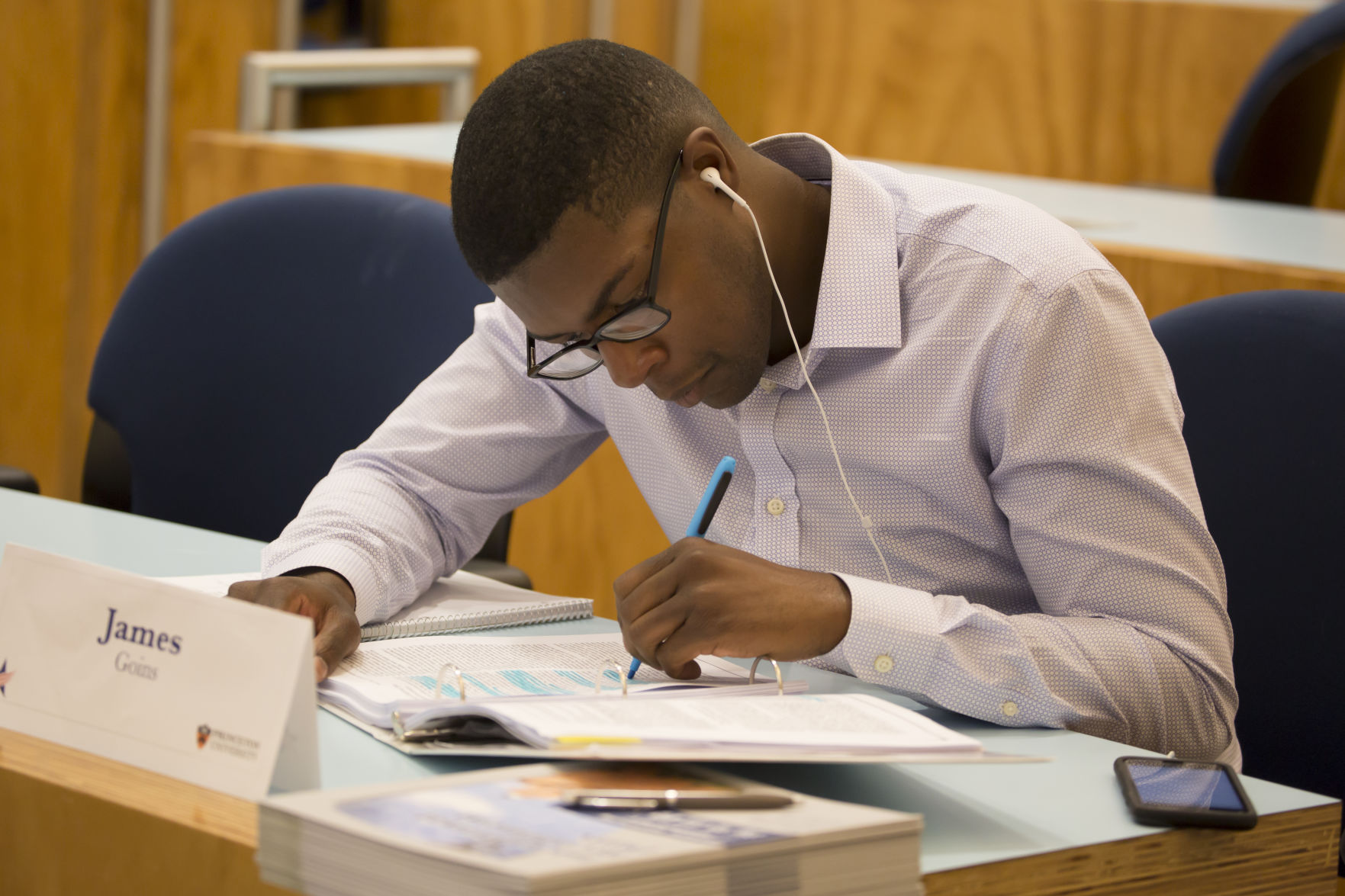

As a teenager, James Goins left civilian life to enter the Air Force, in a decision that meant forgoing attending college. But as he prepares to leave the military next year, Goins, 24, has his mind set on getting into the Ivy League.

To help prepare him for the transition from GI to college student, he and 14 other active duty personnel or veterans looking to readjust to civilian life have spent this week at Princeton University taking an immersive one-week course exposing them to college life and the rigors that go with it.

They have slept in dorms, taken courses taught by university faculty, brushed up on writing skills, gone to study hall, in days that lasted from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m., or 0800 hours to 2200 hours, as they might put it in military time.

They are here through the Warrior-Scholar Project, a nonprofit organization seeking to help GIs in the transition to college. The organization launched a nine-person pilot program at Yale University in 2012, and since has grown to have one or two-week courses at top colleges around the country, like the University of Chicago and the University of Southern California. This was the first year it had come to Princeton.

“So the military does a really wonderful job of taking a young man or a young woman, putting them through boot camp and turning them into a solider or a sailor, (but) not such a good job of turning that person back into a civilian,” said Sidney T. Ellington, executive director of the Warrior-Scholar Project and a retired Navy commander. “So part of what we’re doing is helping them transition back, specifically into higher education and specifically, our program is geared toward getting them with the idea that they can take their GI Bill and attend a top tier school like Princeton.”

As hundreds of thousands of military personnel leave the armed services each year, many of them look to go back to school. With their GI bill to help them pay for tuition, they potentially could help change the face of higher education: older, nontraditional students who are motivated, disciplined, and in many cases, who have experienced war.

In Ellington’s view, they bring a skill-set not seen in typical college students.

“These men and women are team builders, they’re problem-solvers, they’ve got leadership skills, they’re highly adaptable,” Ellington said. “So we believe that you take these attributes, these desires, and you couple it with a top-tier education from a school like Princeton, and what you have laid the foundation for is your civic leaders of tomorrow.”

Holden Lindblom, an Army veteran who acts as a type of drill sergeant to work with the 15 participants, is an alumnus of the program. Growing up in Massachusetts, he was by his own admission a “quite terrible” high school student who nearly dropped out.

“I really just didn’t have motivation or really have my head on straight to be motivated enough to actually get the work done,” he said.

He graduated with what he remembered was either a 1.8 or 2.0 grade point average, and entered the Army looking for structure to help him succeed. He was 17.

Now 24, he served four years, including a combat tour in Afghanistan, in the military. With the skills the Army gave him, he wanted to return to school to “redeem my past failures,” in his words. A few months after getting out in 2015, he attended a two-week Warrior-Scholar course at Yale.

“It was eye-opening,” he said of that experience. “While I was confident that I thought I would do well, I was still very much afraid that I would fall back on my bad habits and that I was almost too far behind.”

With community college credits under his belt, he is due to enter Stanford University in September as a sophomore to major in economics and minor in computer science.

“A lot of the things that I learned within the military translate incredibly well into the academic setting,” he said.

But it is students like Lindblom that top universities have in mind.

Princeton, through its strategic plan, intends to start accepting transfer students. While the university has not announced when that program will start, the aim, in part, is to attract more veterans as undergraduates, said Princeton spokesman Dan Day.

On this Wednesday morning, Goins and the other Warrior-Scholars are taking a course inside Lewis Library, a building designed by architect Frank Gehry and named after a wealthy Princeton University alumnus. In a classroom, Professor Shivaji Sondhi is leading them in a discussion on democracy. Afterward, some said Princeton is on their radar as a school they’d like to attend.

“I think if anyone in there told you that coming here, after stepping on campus for three days, that the thought of attending Princeton didn’t cross their mind, I’d tell you they were lying,” said Bradley Amuso, a 23-year-old Marine, who added he probably would apply to the university.

Goins, a native of Nashville, Tennessee, entered the Air Force as a teenager. As of September, he will have served seven years. Once he leaves, one adjustment of returning to civilian life will be living outside the ordered world of the military.

“I feel almost like you missed out on experiences, like you don’t have the same awareness as everyone else, because you’ve been in such a strict regiment,” he said. “Whereas as most people are very free to explore, you have more like a strict set of the way you’re supposed to live and how you carry yourself. It’s not the same level of freedom, I guess you could say. So I just feel like I’m a little behind the curve as opposed to ahead.”

Due to leave the armed services in 2018, Goins is looking to go to a four-year-college; he’s taken online classes, which he finds to be difficult because he likes the direct contact of being in a classroom asking questions in person.

He plans to apply this year to Princeton and the University of Pennsylvania, his top two choices.

“Both of them, to me, have great (economics) departments, which is my main major I want to do,” Goins said.