EAST BRUNSWICK – Donald Buzney’s mission was to break an ambush at daylight and head to the river, sweeping through a hamlet of about 20 homes.

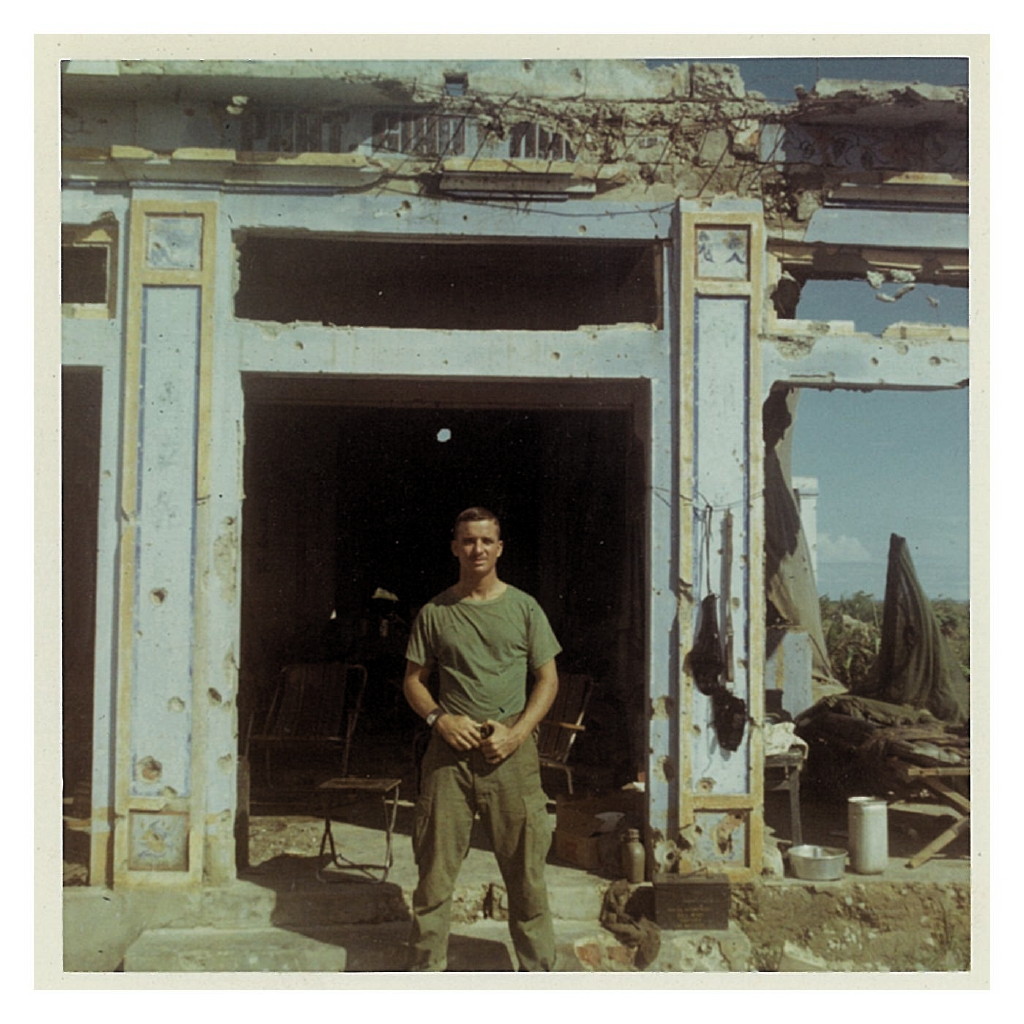

It was 1968 in northern I Corps, just below the DMZ in the Cua Viet region of Vietnam.

“We didn’t like the assignment because we had to walk across an open field,” the second lieutenant in the U.S. Marine Corps recalled.

As his patrol approached the village, a man emerged from one of the huts. He was holding something in the air, seemingly unaware of the impending danger of a group of Marines heading in his direction.

Buzney, who himself wore rosary beads around his neck, realized the man was holding a crucifix, pointing to Buzney’s chain.

“He was animated. He was excited, pointing his cross at my rosary beads, and gesturing for me to enter his home, something I normally would not do,” Buzney said. “But there was something about the look in his eye, something about the look on his face.”

Buzney handed his rifle to another Marine, and entered the man’s house. He observed a few pieces of furniture plus a creche. The man offered tea, a traditional Vietnamese welcome, and then took Buzney by the hand, and on bended knee, began to recite the “Our Father” in Vietnamese.

“He was of military age. I didn’t know what side he was on. But at that point, it didn’t matter. He was praying to end the killing, end the madness,” Buzney said. “Here I was a Marine lieutenant, 7,000 miles away from home, praying with this Vietnamese man to end the war. That stayed with me.”

Buzney joined the Marines in 1967 due to experiences he had in Venezuela, where he spent his childhood.

His father was a civil engineer for Exxon, so Buzney spent ages 3 to 18 in an “idyllic” setting like “Camelot,” he said, “an American community in South America – mom and pop, apple pie, school, and church on Sunday.” He spent nine years in La Salina, an arid and dry area of the country, and then six years in Caripito, which was more verdant and dense jungle.

He learned a different culture, and is fluent in Spanish, “just fitting in” since his family was stationed in an American ccommunity built by the oil company. There was a pool, tennis courts, a golf course and movies twice a week. Buzney said the loudest noise would be a donkey braying.

He and his family would return to the United States every two years for two months, and then every year for a month, visiting relatives in the New York area.

At age 13 Buzney would leave his family from September to June to attend high school in the United States since the educational system was different in Venezuela. He attended the Hackley School in Tarrytown, New York, and the Cardinal Farley Military Academy in Rhinecliff, New York.

“That wasn’t easy,” he said of leaving his immediate family each year.

Long before the advent of the internet, the family would correspond through letters or by using short wave radio. They listened to the “Voice of America” radio show and read a weekly English newspaper from Caracas.

“You do what you have to do because that’s where you are. You have to adapt to it,” Buzney said.

At age 18 he went to Iona College in New Rochelle, New York, and then to St. John’s University in Queens, New York, graduating with a degree political science.

He was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in the Marine Corps in June of 1967. From June 1968 to March 1969 he served in Vietnam as an infantry platoon commander, then spent a few months in Okinawa, Japan.

On his flight home, Buzney recalled the chief pilot of the commercial flight telling the Marines how proud he was to be flying them home. The eastbound flights are always full, but the westbound flights home typically have empty seats, he said. The pilot’s son was a Navy pilot, shot down over North Vietnam and held as a prisoner of war in Vietnam.

Buzney will never forget what the pilot said over the intercom as the flight was nearing its end: “Gentlemen, if you look out the portside cabin window, you’ll see the lights of the western coast of the United States of America.”

“What an experience that was. What an experience,” he said. “You’re relieved to go home but the memories you take with you are not happy ones. It was bittersweet.”

Buzney’s duty station upon returning from Vietnam was the Marine Barracks at the U.S. Naval Base, Great Lakes, Illinois, just north of Chicago.

After separating from the Marines, Buzney used the GI Bill to attend Loyola University in Chicago. He was intrigued by one course on the history of labor unions, and decided to pursue an education in industrial relations, a combination of human resources and labor relations. He eventually earned his Master’s degree from Loyola.

In 1973, Buzney worked for Flagship International, an American Airlines subsidiary in New York City for three years, and then moved to Marriott at the Essex House in New York as the human resources director. He received a call from a headhunter asking if he might be interested in the lead human resources position for Bally’s Park Place, then under construction in Atlantic City. Running the New York City Marathon the day before, Buzney had little interest in trading Central Park South for the Atlantic City of 1980, but his curiosity got the best of him when Las Vegas gaming ambassador Billy Weinberger explained the plans for the new resort area.

Buzney opened Bally’s with 2,000 employees, experiencing three different strikes over 10 years. He was recruited by the Trump Taj Mahal as the vice president of human resources, successfully dealing with a labor shortage since 5,000 employees were needed at the onset.

Buzney continued his career at Native American casinos, spending five years at the Turning Stone Resort Casino in Verona, New York; then Harrah’s Cherokee Casino in North Carolina; and then the Seneca Niagara Resort & Casino in Niagara Falls.

“I enjoyed Native American gaming. It is a different, unique experience. … It’s about the betterment of a people who have been disadvantaged for centuries,” he said.

Buzney has also taken his turn at writing screenplays. “Jenny’s Story” is a love story set in Vietnam, where a career Marine makes a casualty call to notify a widow, and though they go their separate ways they stay in touch, eventually getting married. “Casino Tribe” is about a Native American tribe that goes into gaming but is infiltrated by organized crime. “Plover,” which is he co-writing with two other people, is a satire about political correctness in the business world.

An East Brunswick resident since 2011, Buzney’s more recent hobby has been hosting The Veterans Corner radio show on WRSU Rutgers Radio 88.7 FM at noon on Wednesdays.

He had been active in veterans’ affairs in New York, and talked about doing a radio program with the late Patrick Gualtieri, executive director of the United War Veterans Council, producers of the New York City Veterans Day Parade. Networking led Buzney to the College of Staten Island where he pitched a veterans’ show. Buzney’s wife later suggested he reach out to Rutgers University, which has led to four years and almost 200 programs at WRSU.

He said his favorite guests have included Senator Cory Booker, former Gov. Christie Todd Whitman, a Navajo Code Talker from Arizona, a Marine general who called in from Afghanistan, and a group of students from Linden Public School No. 2 who have been on the air six times with their Principal Atiya Perkins.

Buzney was invited to recite “9-11-2001,” a poem he wrote about the images of the times, during the closing ceremony of Ground Zero in New York. He was working near the headquarters of the Fire Department of New York in Brooklyn, New York, so he dropped off a copy during his lunch hour. The United War Veterans Council was later asked to manage the ceremony for family members, and one of the relatives of a victim of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, asked Buzney to share his poem at the second Ground Zero Closing Ceremony.

He recited the poem from memory on June 2, 2002, at Church and Liberty streets in Manhattan in front of 1,000 people.

Proud to be an American, he said, “that statement itself, it answers itself.”

“No one needs to thank me for my service. I was proud and honored to serve my country as a United States Marine,” he said.

Contact Jennifer Amato at [email protected].