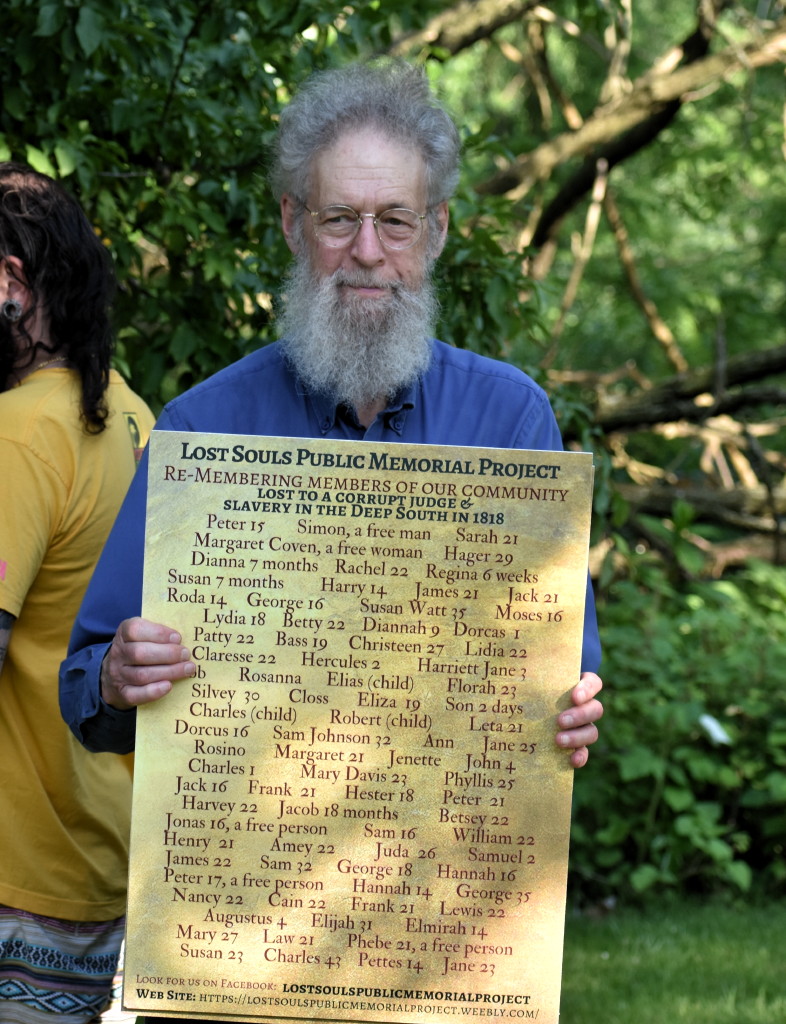

EAST BRUNSWICK–Striving to build a monument to honor victims of Judge Jacob Van Wickle’s slave ring, The Unitarian Society launched the Lost Souls Public Memorial Project.

The project would honor more than 90 African Americans who were sold into slavery by Wickle in 1818, by building a memorial at the East Brunswick Municipal Complex, according to the Rev. Karen Johnston of The Unitarian Society of East Brunswick.

One of the most notorious slave rings to operate in the United States during the first half of the 19th century was in New Jersey, according to a prepared statement regarding the project. In 1818, Wickle was at the center of this ring, which ultimately sent 100 African Americans from New Jersey into slavery in the south.

“We are here today because this is the site of the infamy where the house of [Van Wickle] was and it is my understanding that he held people captive here, so we want to make this ground sacred after it has been defamed,” Johnston said on May 25 at 121 Main St., where Van Wickle used to live.

The project is sponsored by The Unitarian Society, the New Brunswick area branch of the NAACP, the Rutgers University NAACP branch, the New Jersey Chapter of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society, and the Sons and Daughters of the United States Middle Passage, according to historian Richard Walling.

More than 20 locals attended the church’s “re-member” event and helped read the names of the known victims. Afterward, Johnston said a brief prayer to bless the site.

“We gather today to memorialize the souls lost to the diabolical ways of a corrupt Middlesex County judge who lived here on this piece of land. Judge Jacob Van Wickle abused his office and signed nearly 100 African Americans into permanent slavery in the deep south [by] three known boatloads,” Johnston said. “The first sailed on March 10, 1818, and the second on [May 25, 1818], 200 years ago exactly today. I say three known boat loads and I say 91 known names, six of which have only become known to us in the last 24 hours thanks to the research of [resident] Richard Walling.”

Johnston said there is a very real possibility there were more boats with fraudulent manifests that shipped African Americans, but their names were not recorded.

“We shifted to the idea of building up a memorial rather than taking down the [street] sign that is named after [Van Wickle]. It really is about 2018 [and] recognizing that there is this 200-year anniversary and it’s a key time for us to remember,” Johnston said.

In February, the Unitarian Society held its first major event, a panel discussion that looked at the history of the site.

“We are having at least three of these events. The first one coincided with Black History Month, but also the first boat that took people away. Today coincides with the second boat [which] sailed 200 years ago today that people into permanent slavery. The third boatload went sometime in October, we are not actually sure when, but our intention is to have another big event then,” Johnston said.

Johnston said locals participating in the community effort have been in communication with the township administrator and are hoping to have it located at the municipal complex.

“It is our understanding that they are open to that idea. In terms of what [the memorial] will look like, that’s actually very dynamic. We are so lucky that we have students this summer from the landscape architecture at Rutgers University who are going to help us imagine what the possibilities are.”

During the event, locals also took photos, taking the pledge and “re-membering” the victims in the community.

“I am thrilled at how many people came out, folks that we have not had contact with. My congregation wants to be a conduit for a community effort,” Johnston said. “We would really love to have it be a chance for other people to come together and to take this up, because we think everyone, no matter where they stand politically, no matter what they identify racially, this is something we should care about all throughout central New Jersey.”

Walling said, “It just goes to show that people of good will of every background, we all honor our ancestors, and collectively, the folks that were out here, we are all Americans, and this is a slice of American history that was deliberately swept under the rug, but now we are exposing it to light.”

Resident Peter Kahn said while he was in Berlin this past summer, his friends took him to a disused railroad siding in the far western part of the city that was heavily used until the end of World War II.

“When the Nazis would deport Jews from Berlin, most of those Jews lived in the eastern part of the city and there are many railways in which they would have been sent east to the extermination camps. Instead, they were trucked to far western railroad sidings, which was in the wealthy part of the city then and now,” he said.

Kahn said the Nazis feared that if the working class neighbors of those people would see what was happening, they would rise up and protest; the Nazis did not want that, so thousands of people were sent to that railroad siding. It is no longer used for rail traffic but is now a memorial, and along the tracks there are pleats that list the number of people who were sent to the extermination camps, the date they were sent and the name of the camp they were sent to, he said.

“I had been there this past summer and when we came home and I found out about the idea to first rename [Van Wickle] road. I realized what would happen is if we were to succeed in renaming Van Wickle Road the whole history would be forgotten. The creation of the memorial is a way not to forget,” Kahn said.

“If you don’t remember you forget, and if a community doesn’t remember it forgets and if it forgets … its past will come back to haunt it,” Kahn said.

For more information about the Lost Souls Public Memorial Project, visit www.lostsoulspublicmemorialproject.weebly.com/about.html or its Facebook page.

Contact Vashti Harris at [email protected].