By Jimin Kang

Contributor

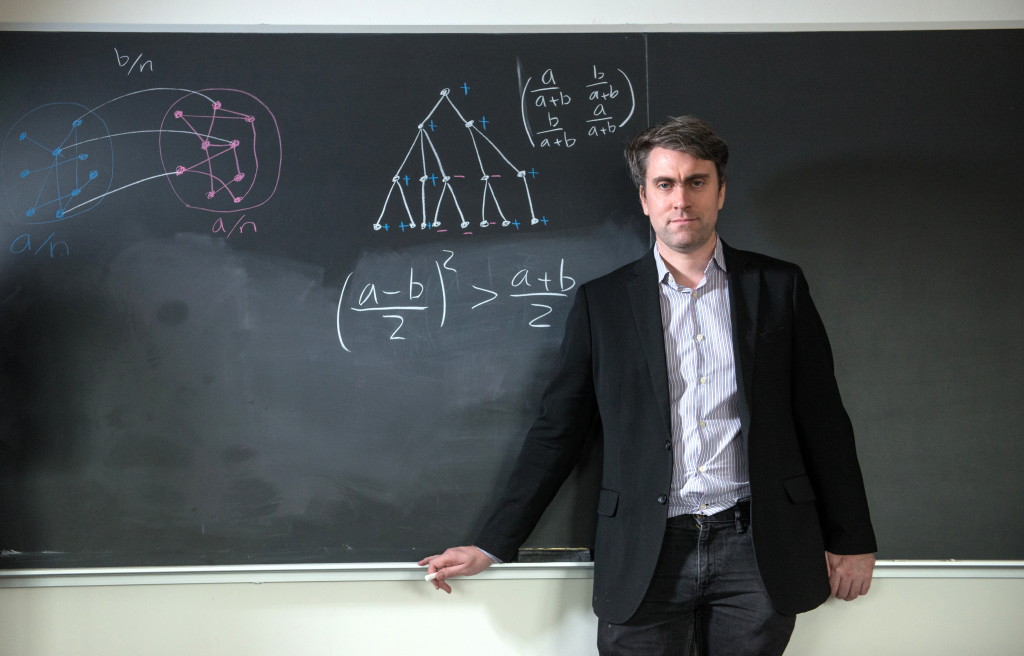

Professor Allan Sly, 36, was in his office when he received a call from the MacArthur Foundation congratulating him on his new “Genius” Grant. The situation was “too elaborate” to be a prank, he thought.

“Almost no one ever calls the phone in my office,” Sly, who teaches Mathematics at Princeton University, said. “So that was already a surprise.”

Associate professor Clifford Brangwynne, 40, received a similar surprise—but at the gym.

“I was sitting down at one of those rowing type machines,” said Brangwynne, who is an associate professor in Princeton’s Chemical and Biological Engineering Department. “The call came and I actually fumbled with the phone and hung up accidentally. Pretty overwhelming, as you can imagine.”

The MacArthur Fellowship, informally known as the MacArthur “Genius” Grant, is a prize awarded annually by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation to anywhere between 20 and 30 individuals who have shown “extraordinary originality and dedication” in their “creative pursuits.” Awardees can use the “no-strings-attached” prize of $625,000 in any way they wish. The program does not accept applications or unsolicited nominations. Nominees are flagged by a “constantly changing pool” of nominators to maintain the mystery behind the award.

This year, the award was presented to 25 people from a diverse range of professions including journalism, art, academia and social advocacy. For the first time in at least ten years, two of the recipients are based in the town of Princeton—an astonishing feat for a prestigious national award.

***

Allan Sly, mathematician and Princeton resident, has taught Mathematics at Princeton University since 2016. He is a specialist in probability theory, a field which he used to find “boring” in high school but developed an interest in during an internship after his first year of college.

For those unfamiliar with the field, he would describe his work as the discovery of “clusters” within networks—like figuring out people’s party affiliations by studying their friendships.

Imagine, he said, a room full of Republicans and Democrats.

“You imagine you’re more likely to be friends with someone in your own party, but you’d also have friends on the other side,” he said. If someone from the outside observes the friendships, can they work out who was in each party based on the structures within the network?

“This is a kind of natural statistical problem of ‘clustering’ in a sense,” said Sly, who has been working on a “mathematical idealization” of the problem and has been “interested in math” for as long as he can remember.

Sometimes, when he and his wife, Professor Daisy Yan Huang at the Center for Statistics and Machine Learning at Princeton, go to dinner with her Cantonese-speaking extended family, Sly—who doesn’t speak Cantonese—sits quietly “thinking of math problems.”

Before coming to Princeton with Huang, Sly taught statistics at his alma mater, the University of California at Berkeley, where he received his PhD back in 2009.

Sly and Huang bought a house in Princeton last December after spending a year in University housing. For the Canberra, Australia native who had just moved from Berkeley, California, the first winter as a Princeton homeowner was difficult—but not without some pleasant surprises.

“We bought a house in December and a couple of days later I found myself shoveling snow for the first time,” said Sly. “You sort of see the neighbors doing the same… and so I met the other people on the street at the same time.

“It’s nice being in a neighborhood where people know their neighbors. It reminded me a bit of Canberra and where I grew up.”

When not at Princeton, Sly is frequently overseas for conferences. Over the summer he was in Lithuania, the United Kingdom and Brazil, where in Rio de Janeiro he witnessed the theft of one of the four Fields Medals—regarded as the ‘Nobel Prize’ for math—back in August.

“A couple of days later they awarded him a new one, so there were all these jokes that he was the only one to win two medals,” said Sly, referring to Caucher Birkar, a UK-based mathematician whose medal was stolen.

Sly is taking a sabbatical from Princeton next semester, during which he will travel to Stanford, MIT, India and Paris. The first PhD student he advised in his career will be hosting a conference in Bangalore.

“It’s very nice when your students have been successful,” he said, “and you come visit them in interesting places.”

While he is still at Princeton, however, Sly will engage in his usual hobbies: going for walks, reading news on the internet and eating out at restaurants (he and his wife are frequent visitors at Witherspoon Grill and Eno Terra).

“I feel very boring when people ask this,” said Sly, laughing, referring to questions about his hobbies.

***

Clifford Brangwynne, a biophysical engineer, lives in Hopewell with his wife, Sarah Brangwynne, and their three children. He currently serves as an investigator for the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, a philanthropic institution that attempts to “radically advance” knowledge in human biology.

“Organelles are to the cell what organs are to our bodies,” said Brangwynne, whose work deals with the process of cell compartmentalization. “It’s still pretty poorly understood how they’re assembled.”

Brangwynne, who was born and raised in the Boston area, received his PhD in Applied Physics at Harvard University after studying Material Science Engineering at Carnegie Mellon. He started doing biological work—the basis of the research he does today—during his post-doctoral research in Germany.

“I’ve been interested in the contents of the cell and what it feels like,” he said. “Biological systems are the most interesting organizations of matter of atoms and molecules in the universe. It’s the basis for everything we know and love.”

Like Sly, Brangwynne has traveled internationally for work—or, in some cases, for his sheer “love of adventure.” He once traveled to Latin America where he had a “mini-Peace Corps” experience through the Amigos de las Americas program in high school.

Mentorship is important for Brangwynne, who on campus advises freshmen on course selection and seniors on their theses. Mentorship, he thinks, is what helped him overcome self-doubt, a feeling that he considers as one of the biggest challenges of his career.

“At the brink of scientific discovery, things can look pretty bleak,” he said, “and so I wonder how many discoveries have not happened because things looked bleak right before.”

Brangwynne’s financial situation during his young adulthood was another challenge he struggled with early on in his career. Having been raised in a working-class background, Brangwynne said, he was “really poor” during his undergraduate years at Carnegie Mellon.

“It was a trying to survive type of thing,” said Brangwynne.

He also spoke of difficulties of not having immediate examples to turn to in his family.

“I didn’t have any examples in my family of people who had gone through professional schools and gotten PhDs and things like that,” he said. “At the same time, my parents still very much valued education and instilled that in me.”

Brangwynne’s sister, Christin Brangwynne Khan, 43, is also a researcher. She is a marine biologist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration where she studies the endangered right whale.

Although Brangwynne is “most excited” by scientific discovery, there are other things on his bucket list: like flying a plane or writing a work of fiction.

“I’m a big fan of doing things outside your comfort zone,” he said. “I think that’s where a lot of progress happens.”

***

In our lifetimes, not many of us can expect to receive a six-figure grant and know exactly what to do with it.

Sly and Brangwynne aren’t exceptions. Both professors aren’t really sure what they want to do with the award—but for good reasons.

“After a while, you look back and see how just small things change the direction of where you end up, so it’s very hard to know what problems I’ll be thinking about in five years’ time,” said Sly. “[I] hope that there will be things I haven’t even thought of thinking about today. Otherwise it wouldn’t be exciting.”

Brangwynne had a similar response.

“I hope that what I’m doing in 15 years, let’s say, let alone 40… I hope that that is something so different from what I’m doing now that I can’t even conceive of it right now,” he said. “And the reason for that is that there’s a tendency in the sciences, and maybe in all fields, to do what one is comfortable with. I’d much rather break into new territory even if that’s an uncomfortable process.”