A teenager from Marlboro is using science to convert experience into awareness.

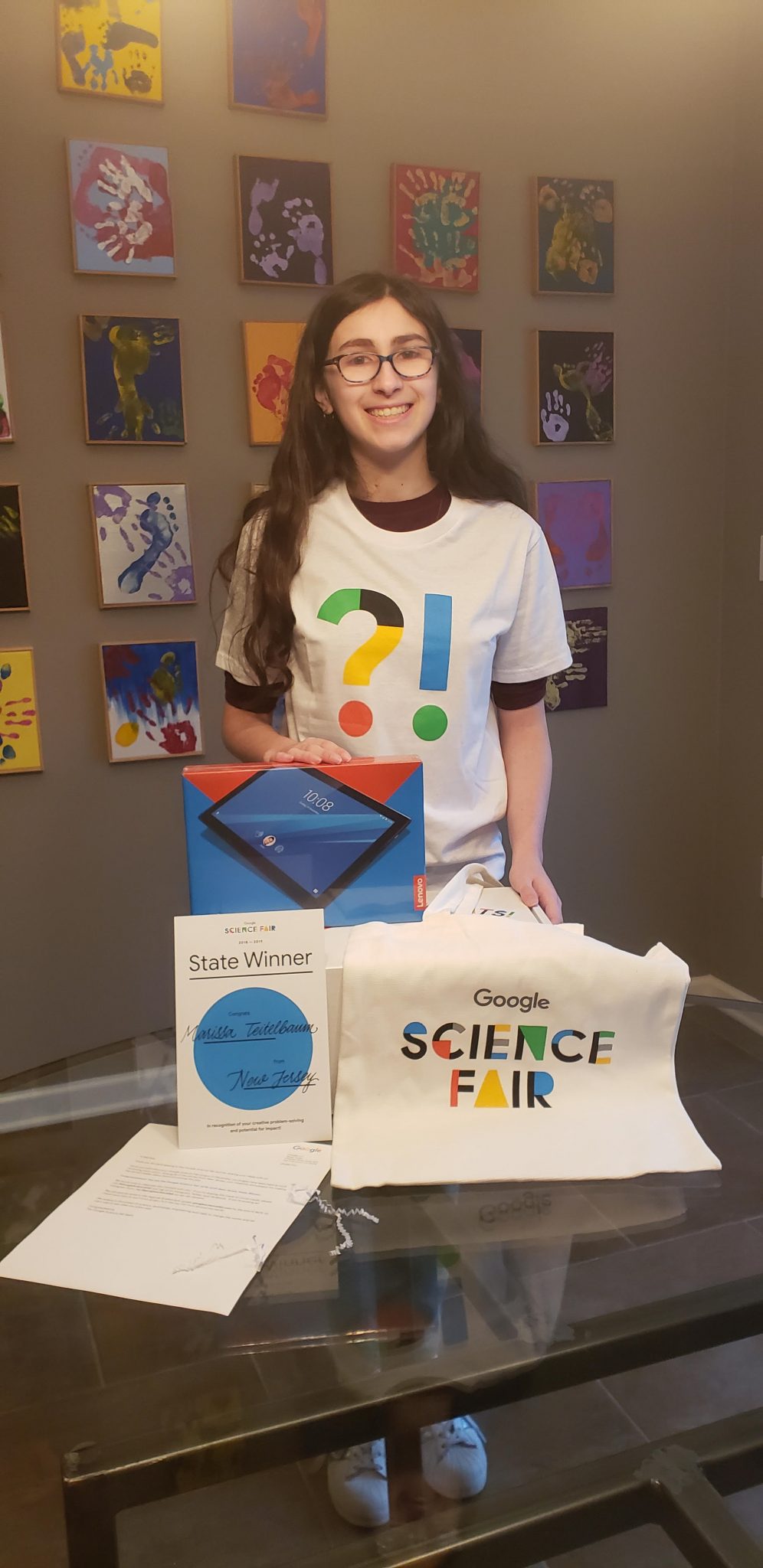

Marissa Teitelbaum, 16, a sophomore at High Technology High School, which is located in Lincroft, has been named a regional winner of the Google Science Fair.

The Google Science Fair is an international online science competition, which is open to students between the ages of 13 and 18.

Marissa’s project, “Alteration of Bicycle Handlebar Grips to Decrease Impact as Measured by Penetration into Ballistic Gelatin,” has been selected as one of the top 100 projects that were submitted during the international competition.

The young woman’s project will now advance to the next round of judging. A panel of professionals will further evaluate her research which analyzes the impact bicycle handle grips could have if a handlebar accidentally acts as a “blunt spear” on an individual’s abdomen while that person is riding a bicycle.

In an interview, Marissa said her neighbor suffered a direct contact injury when the handlebar of the bicycle he was riding plunged into his abdomen, damaging his spleen. The injury inspired Marissa to pursue a solution to what she called “a dangerous issue.”

“If the front wheel of the bicycle gets caught and the bike turns, your momentum would cause you to go into the (handlebar) grip,” she said. “Like a blunt spear, (the handlebar) stabs into your stomach … This can cause a lot of internal injuries, especially since there are a lot of internal organs there.”

Marissa said she created a 10-foot tall mechanism with a sliding platform and a wooden base. One of three handlebars were attached to a 7-pound weight and released, landing on a slab of ballistic gelatin, which is a testing medium that replicates muscle tissue.

Marissa said she tested a standard set of handlebar grips, then grips she created with a three-dimensional printer and finally a wider set of grips she also created on a three-dimensional printer. She dropped each grip 12 times onto the ballistic gelatin.

She said the wide-end 3-D printed grip performed the best. She said that grip penetrated 1.5 inches into the ballistic gelatin when it was dropped, while the other two grips each penetrated 3 inches into the ballistic gelatin.

“What I tested was my idea for a grip which increased the surface area at the end of the grip. (This grip) distributed the force more,” Marissa said. “This means the grip wouldn’t go as deep into your stomach and hit major organs as hard … In terms of variables, I could say the difference was (the high performing grip) was wider.

“… When I compared the similar dimensions of the rubber (grips), there was no difference. That means the rubber (the store) made the grips out of, and the plastic I made the grips out of did not affect how deep the grip went” into the ballistic gelatin, she said.

According to Marissa’s research statement, “Bicycle accidents are one of the major causes of unintentional traumatic injury in children. Direct-impact injuries from bicycle handlebars lead to worse outcomes than people who sustained an injury by flipping over the handle bar.”

Marissa said she hopes the conclusions she has drawn from her bicycle handlebar project encourage other students to pursue solutions to everyday problems.

The young woman has been busy this spring.

On April 29, Marissa presented her research findings on a separate issue during an appearance before the Pediatric Academic Societies in Baltimore, Md.

Marissa, who broke her arm when she fell off monkey bars as child, said that experience inspired her to research the number of children who injure their arms on playground equipment each year.

“I got approval to go through charts at my orthepedic (doctor’s) office and find people who hurt themselves on monkey bars,” she explained. “Since (the accident), I have developed this project for seven years … I went through the charts and found all the people who hurt themselves on monkey bars.”

Marissa was granted access to medical documents by the Institutional Review Board, an administrative body established to protect the rights and welfare of human research subjects recruited to participate in research activities conducted under the auspices of the institution with which it is affiliated, according to the board.

After Marissa identified 991 children who hurt their arms on monkey bars in 2017, she contacted the children’s parents and traveled to 29 locations where the identified children injured their arms on playground equipment.

“I had my mom drive me to all of the places we were able to identify,” Marissa said. “I measured how high up the monkey bars were. Some studies say the ground cover, as long as it is not concrete, doesn’t make much of a difference. I measured how high (the monkey bars) were and the distance between them. I also (measured) the circumference of the grip because most of the kids who hurt themselves were 6.”

Marissa said she compared the heights of the monkey bars to the heights recommended by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission for preschool and school-age children.

“When I compared (heights), most of the (monkey bars), at least for preschool (children), were higher. A lot of the current monkey bars for these age groups ended up being higher than they should have been,” she said.

Marissa said she may encourage the American Academy of Pediatrics to publish a formal statement which outlines the potential dangers of monkey bars. Based on a European study, monkey bars should not be taller than 59 inches in order to reduce the likelihood of injury, she said.