By Pam Hersh

In this time of high angst over the state of our democracy, job security, fiscal resources, housing insecurity/potential eviction, and, of course, our health during a raging pandemic, I have had the best time going to a party, albeit a virtual one. The celebration is known as a “rent party,” an annual event hosted by Housing Initiatives of Princeton (HIP). It all sounds like a cruel oxymoron, since celebratory party and rent and eviction and pandemic are words that seem completely at odds with one another.

But it all makes perfect sense to those aficionados of Housing Initiatives of Princeton, which since 2004 has been helping low-income families avoid homelessness by providing service-enriched transitional housing and rental assistance programs. I always thought that HIP’s annual rent party was simply a vehicle to raise money so HIP could help its clients, on the verge of becoming homeless, pay their rent. My epiphany about rent parties occurred, however, after a conversation I had with Princeton University’s Wallace Best, a featured guest at this year’s HIP Rent Party.

The director of the university’s Gender and Sexuality Studies Program and professor of religion and African American studies, Dr. Best explained that “in 2020, HIP’s rent party, is a fundraiser to benefit those whose lives are threatened by the loss of their home, but it also is so much more. It has a rich history and reflects community and humanity at their best.”

A rent party, according to Professor Best, a specialist in African American religious history of the 19th and 20th centuries, is no new phenomenon. Born in the 1920s in Harlem, the rent party was a joyful community gathering hosted by tenants who were having problems paying their rent. The rent-insecure tenants would arrange for food and drink and live musicians at a time when Harlem, a very tight-knit community, was blessed with incredible musical talent. The host would invite people of all ages and backgrounds to come together for dancing, drinking, eating and joyful socializing. There was a small entrance fee and the proceeds were used to pay the host’s rent.

Rent parties had a “curious dual function” said Professor Best, who noted his own family’s housing insecurity of his youth in Washington, D.C.

“Its first purpose was to provide a good time on Friday or Saturday night; the parties were known to be the highlight of the week. … And of course, the second purpose was to keep people in their home. But the overarching quality of the parties was community – people helping their neighbors, people enjoying their friends and neighbors. No one was embarrassed to need help, no one felt awkward giving help. In fact, people were eager to help – and to have such a good time at the same time.”

Black tenants in Harlem during the 1920s and 1930s faced discriminatory rental rates. That, along with the generally lower salaries for Black workers, created a situation in which many people were short of rent money. The rent parties were originally meant to bridge that gap.

“Rent parties were the great equalizer, mixing all economic classes – physicians and the janitors danced next to one another with equal amounts of joy,” he said.

Professor Best became enamored with the rent party concept, when he was researching the writings of Langston Hughes, the internationally renowned American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright and columnist. Professor Best discovered Harlem through the eyes of Langston Hughes, who painted Harlem with words that left an indelible imprint upon the sensibility of Dr. Best.

“Rent parties fascinated Langston Hughes – and as a result I became fascinated as well. Rent parties seemed to disappear after the Depression but returned in the post-war era – with a little less pizzazz because the parties featured recorded music rather than live music from Harlem’s legendary jazz talents,” Dr. Best said.

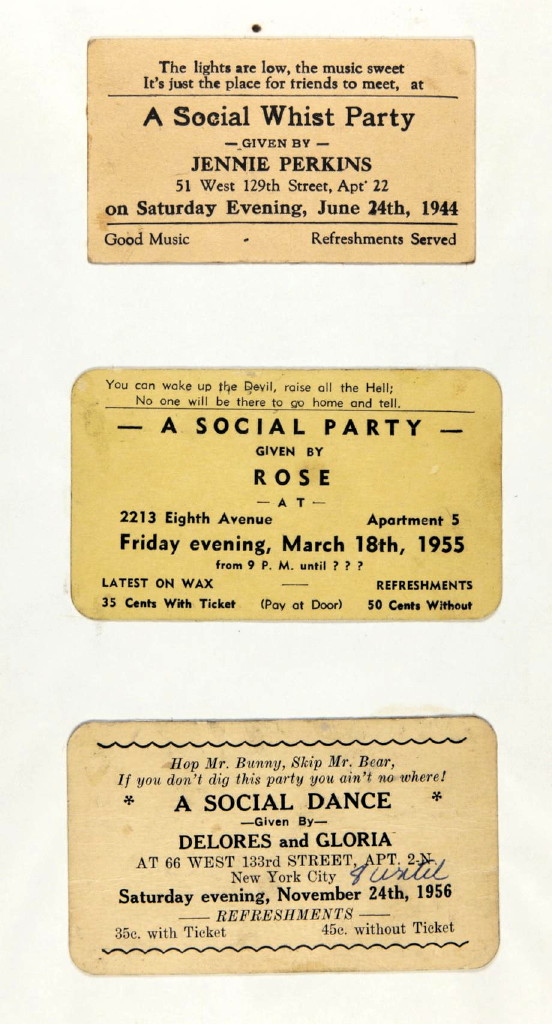

Mr. Hughes collected Harlem Rent Party cards that advertised the parties and the featured musical entertainment at the party. At the top of the cards were lyrics from popular songs or made-up rhyming verses that intrigued the poet Langston Hughes, who considered these cards a physical manifestation of the Harlem he knew and loved so well.

Translating the Harlem Rent Party of the 1920s to modern day Princeton, particularly during a pandemic, is somewhat of a “challenge, but in fact, the Rent Parties are more important than ever before in HIPs history,” said Carol Golden, chair of HIP. The 2020 rent party maybe is different from the rent party in the 1920s, but the underlying principle of the event is the same – “neighbors helping neighbors with rent in times of need.”

The series of Rent Party videos featuring speakers and jazz music is no substitute for an in-person gathering of people, but it has served the valuable goal of entertaining participants while informing people of “the dire need to respond to housing insecurity,” said Ms. Golden.

In New Jersey, since 1960, rents have risen 61 percent, while incomes have only grown by 5 percent. Half of New Jersey’s one million renters are worried about making the rent. We know housing is health — and the COVID-19 crisis has confirmed it. Access to a safe and affordable home during this pandemic has literally been a matter of life and death, she noted. And a rent party may be just what the doctor – and the musician – ordered.

To participate in HIP’s virtual Rent Party

https://housinginitiativesofprinceton.org/