By Jeff Pfeiffer

Among the fictional Maine communities that author Stephen King has created for his stories, the town of Jerusalem’s Lot stands out with an evil energy that has long made it a magnet for malevolent forces like the vampire who arrives in King’s 1975 novel ‘Salem’s Lot.’

A few years after that book, King published a sort of prequel, the short story “Jerusalem’s Lot,” which takes place mostly in the 19th century and offers a glimpse of the hamlet’s infamous past.

That story serves as the inspiration for the new EPIX series Chapelwaite, a 10-episode hourlong drama that is one of the most effectively horrific adaptations of a King work. The series debuted last week, and continues its Sunday night airings this week with the second episode, “Memento Mori.”

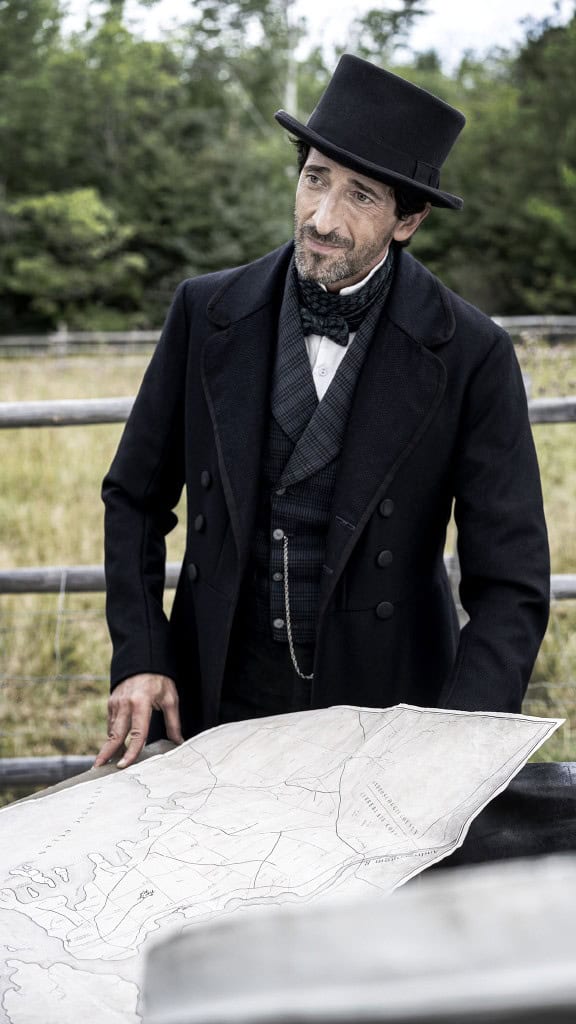

Oscar winner Adrien Brody (pictured; also an executive producer) and Emily Hampshire (Schitt’s Creek) lead this grim and gothic tale. Set in the 1850s, it follows Capt. Charles Boone (Brody), who relocates his family of three children to his ancestral home of Chapelwaite in the small town of Preacher’s Corners, Maine, after his wife dies at sea. However, Charles will soon have to confront the secrets of his family’s sordid history and fight to end the darkness that has plagued the Boones for generations.

It’s especially impressive that King’s story has been adapted so compellingly here given that “Jerusalem’s Lot” is an epistolary tale — its action is related through characters’ letters and journal entries, a challenging technique to effectively write, let alone adapt.

Much of the credit goes to Chapelwaite showrunners Peter and Jason Filardi, brothers and screenwriters/producers who are teaming for their first project together here. While Jason has mostly worked with comedy projects prior to this, Peter has written a couple of cult horror films — Flatliners (1990) and The Craft (1996) — and is no stranger to the world of Stephen King, having written two episodes of the 2004 Salem’s Lot miniseries.

“We’re both lifelong fans [of King],” Peter says. “[After] reading [“Jerusalem’s Lot”], it was a matter of tapping into the theme of it all, and the world of it all, and then sort of building it out from there.”

With their creative team, the Filardis have indeed built out a world in Chapelwaite that not only captures the atmosphere of King’s story, but also incorporates imagery and tropes of classic gothic tales. Those range from the old dark house of the title itself to the governess (Hampshire) who comes to work for its owner, a brooding man with dark secrets — and perhaps madness, given his tendency to hear what he thinks are rats scratching behind the walls, and the grotesque visions he has involving lots of squirming earthworms.

It’s a world that unfolds with enough of a slow burn to create a persistent and increasing sense of dread, and even fans knowledgeable with King’s works will find shocks as the secrets of Chapelwaite, Preacher’s Corners and the nearby Jerusalem’s Lot are revealed.

“We felt very much that the original story itself had that gothic feel built in,” Jason says. “Both of us are huge fans of gothic horror stories, so we capitalized on what was already there and built and expanded.”

Peter explains that “King has carved out such a giant place for himself in the haunted house genre with The Shining, that when you combine gothic horror [with something like that,] it’s a fun mashup. The original story, a lot of it is Stephen King’s nod to [H.P.] Lovecraft. And so, it’s almost like the series [blends together] a long lineage of gothic horror.”

It isn’t only the Chapelwaite house that holds terrors. Shot in Nova Scotia as a stand-in for Maine, the series uses terrific cinematography to vividly re-create just how frightening the outdoors and the nighttime could be for people living in what was basically still a wilderness in the days before electricity.

“We wanted the show to look and feel like real life of that time,” Jason says of the series’ naturalistic feel that enhances its scariness even in daylight. “A big discussion we had was, let’s use natural lighting as much as we can. And when there’s lighting, let’s use the lamplight. Back then, it would’ve been probably oil lamps, so that figures into our story.”

“We also spoke,” adds Peter, “about light as a character in this story. Charles Boone was a whaler, and he would bring back whale oil, which was used in lamps to create light and push back against the shadows. Metaphorically, he’s pushing back against superstition and fear and prejudice and a lot of other things. … The idea of light and shadow and ignorance and knowledge and all that Charles is bringing to this small town was a big thematic element that we wanted.”