One of Dr. Stephen Felton’s earliest childhood memories is that of standing on the deck of a ship in New York Harbor, staring at the lighting on the Statue of Liberty and watching the twinkling lights on the land.

It was cold and snow was on the way, but Felton, who was 5 years old in 1947, was transfixed by what he saw. He didn’t know it at the time, but the twinkling lights were car headlights on the Belt Parkway that links Brooklyn and Queens in New York City.

Felton, his mother and his stepfather were preparing to land in the United States and start fresh, after six years of avoiding Nazi soldiers and the near-certainty of hard labor or death in the Nazi concentration camps.

They were Holocaust survivors.

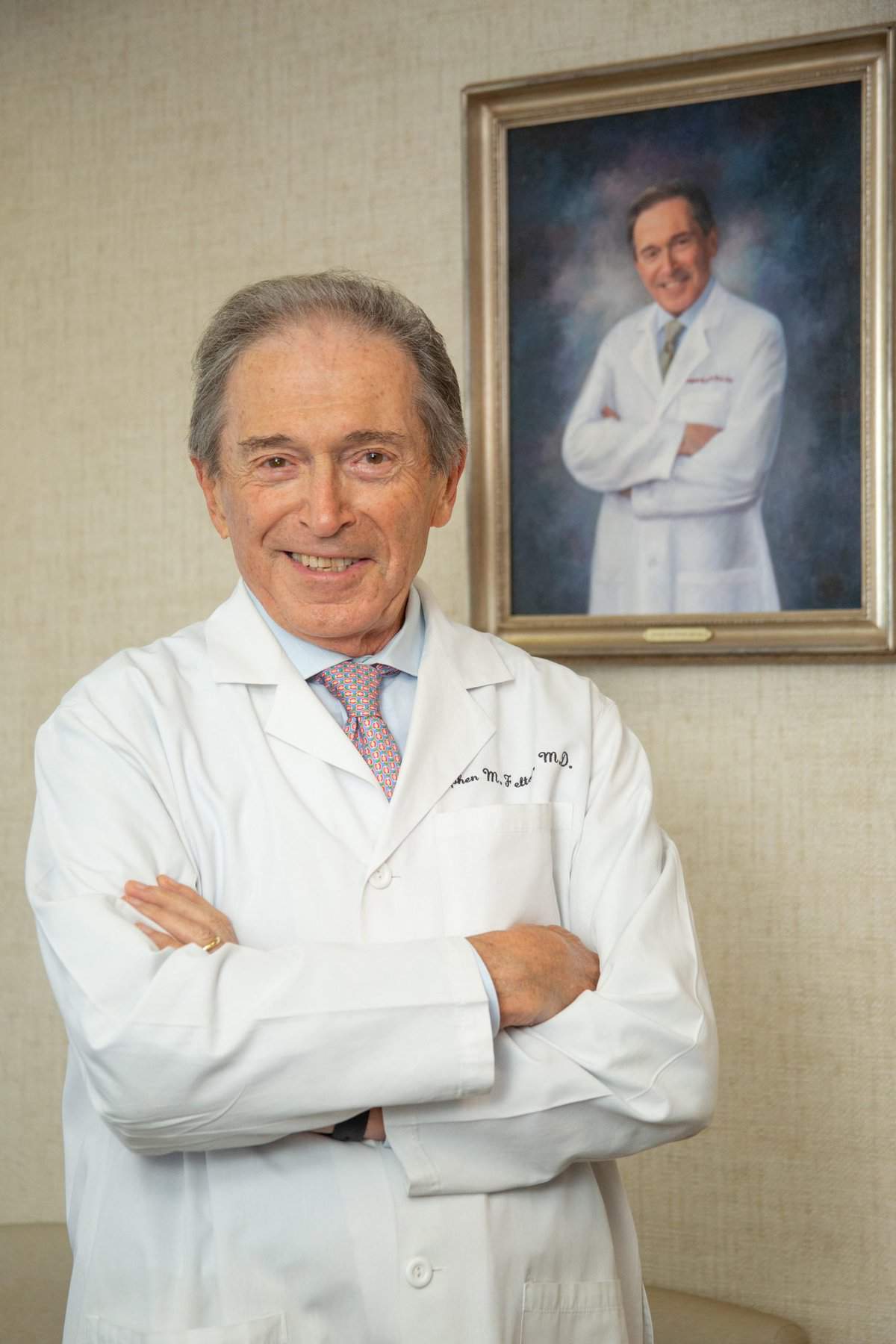

“(Arriving in the U.S.) meant joy and freedom,” said Felton, who retired from the Princeton Eye Group Sept. 1 after a 40-year career. He is the founder of the ophthalmology group, which has offices in Princeton, Somerset and Monroe Township.

“America is everything I thought it would be. It was unbelievable. It’s really a beautiful thing,” Felton said of the U.S., which also allowed him to flourish and to attend medical school to become an ophthalmologist.

Felton’s story begins in the ghetto in Warsaw, Poland, where he was born in 1942. His mother’s father and her siblings had been killed by the Nazis, and she was distraught, he said. She was advised to have “a baby” to have something to live for, he said.

Felton was that baby. He lived with his parents and stepbrother in the Warsaw ghetto, where the Jews were segregated from the rest of society by the Nazis. Spurred by the deteriorating conditions, his father arranged for Felton and his mother to be smuggled out of the ghetto.

But Felton’s father and stepbrother were unable to escape. They were killed in the Auschwitz concentration camp.

Felton and his mother went into hiding, moving from place to place. His mother had several encounters with the Nazis, who suspected – but could not prove – that she was Jewish. She dyed her hair and transformed herself into a Polish Catholic woman, complete with forged identity papers.

Toward the end of the war, Felton and his mother were protected by the Matacz family. His mother had a close friend in grade school, whose brother was a Polish police officer. She remembered that her friend told her to find him if she ever needed help.

Felton’s mother found Stefan Matacz, the Polish police officer. Members of the extended Matacz family – the police officer’s brothers, their mother and their aunt – gave them shelter and helped them to move from place to place to avoid the Nazis, risking their own lives.

“(Stefan Matacz) and his family protected us. We went from one Matacz family to another Matacz family. People got suspicious if you stayed too long, so we had to move,” Felton said.

Felton and his mother spent the last years of the war living with Stefan Matacz’s wife and children in a small village, pretending to be family members. Stefan Matacz had moved his family from their home in Lublin to a small nearby village for their safety.

For their efforts, the Matacz family was honored by Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem, Israel. They were included in the list of “Righteous Among the Nations,” which is an honor bestowed by Yad Vashem on Christians who risked their own lives to save Jews during the Holocaust.

After World War II ended, his mother married another Holocaust survivor, Felton said. They moved to Paris and eventually emigrated to the U.S., he said. His biological father’s uncle had moved to the U.S. in the 1920s and agreed to sponsor the family.

Felton said that he, his mother and his stepfather settled in Brooklyn, N.Y. He earned a bachelor’s degree from Brooklyn College, and a Ph.D. in chemistry from Rutgers University. He worked for his uncle, who was his role model, at the Felton Chemical Co.

While he worked for his uncle, Felton said, he was not satisfied and wanted to do more.

“I was bored. I felt I was not really helping humanity. I really wanted to be a doctor,” he said.

So despite his mother’s misgivings, he applied to the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey and was accepted to medical school.

After completing medical school, Felton decided to specialize in ophthalmology, which is the study of the eye and its diseases. He trained at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia, which was established almost 200 years ago in 1832.

The specialty appealed to him because it offers a good combination of internal medicine and surgery, he said.

“It’s a wonderful specialty with mostly happy patients. Restoring vision with cataract surgery and LASIK has been very satisfying to me and to my patients,” Felton said.

When he was ready to begin practicing medicine after completing his training, Felton considered joining an existing medical practice. He said he realized that his training at Wills Eye Hospital was “exceptional,” and decided to start his own practice.

Felton said he had met some doctors at Princeton Hospital and arranged to sublet one room in a doctor’s office where he could begin his own practice. For the first week or two of his practice, all of his patients were his friends, he said. Soon, the practice began to grow.

“After two years of being on my own, I realized that having a partner to share my responsibilities and to meet the needs of the community was the way to proceed,” he said.

Felton, who was teaching medical residents at Wills Eye Hospital, reached out to one of those residents – Dr. Michael Wong – and invited him to join the practice after he completed his training. The two physicians joined forces and began to expand the Princeton Eye Group.

The Princeton Eye Group expanded to include 10 ophthalmologists – many of whom trained at Wills Eye Hospital – and four optometrists who earned Doctor of Optometry degrees. They can provide many of the services that ophthalmologists do, with the exception of surgery.

The Princeton Eye Group offers one ambulatory surgical center for specialty eye care, as well as the three offices in Princeton, Somerset and Monroe Township.

“I think this is far beyond what I ever expected when I started my practice. I look back and I think, ‘Did I really do this?’” Felton said.

The few months leading up to his retirement were difficult, he said. Patients came to the office to say goodbye. Many times, there were kisses and hugs because “these are people I have taken care of for 40 years. We talked about their lives and you get to know people very well.”

Now that he has retired, Felton said he is going to spend more time with his children and grandchildren. He said that he and his wife like to travel, play bridge and play golf. There will be more time to engage in those activities, he said.

Felton said he would also like to spend more time researching his family history and to continue his mother’s legacy in documenting their mutual Holocaust history. His mother, Eva Feldsztein, had written a memoir of her experiences during the Holocaust.