Ultimate Peace holds first summer camp at The Lawrenceville School

David Barkan believes the key to peace lies in a Frisbee disc.

Barkan, the founder and executive director of Ultimate Peace, uses the sport of ultimate – formerly known as Ultimate Frisbee – to bring young people together as teammates and as newly found friends.

Barkan has run Ultimate Peace camps and leadership programs in the Middle East for several years, and now he has brought the program to the United States.

About 80 campers spent seven days on The Lawrenceville School campus in Lawrence Township during the first week of July for the inaugural U.S. Ultimate Peace camp.

The Ultimate Peace camp brought together high school-aged youths from across the United States and from varied backgrounds to play on ultimate teams. They came from big cities and small towns.

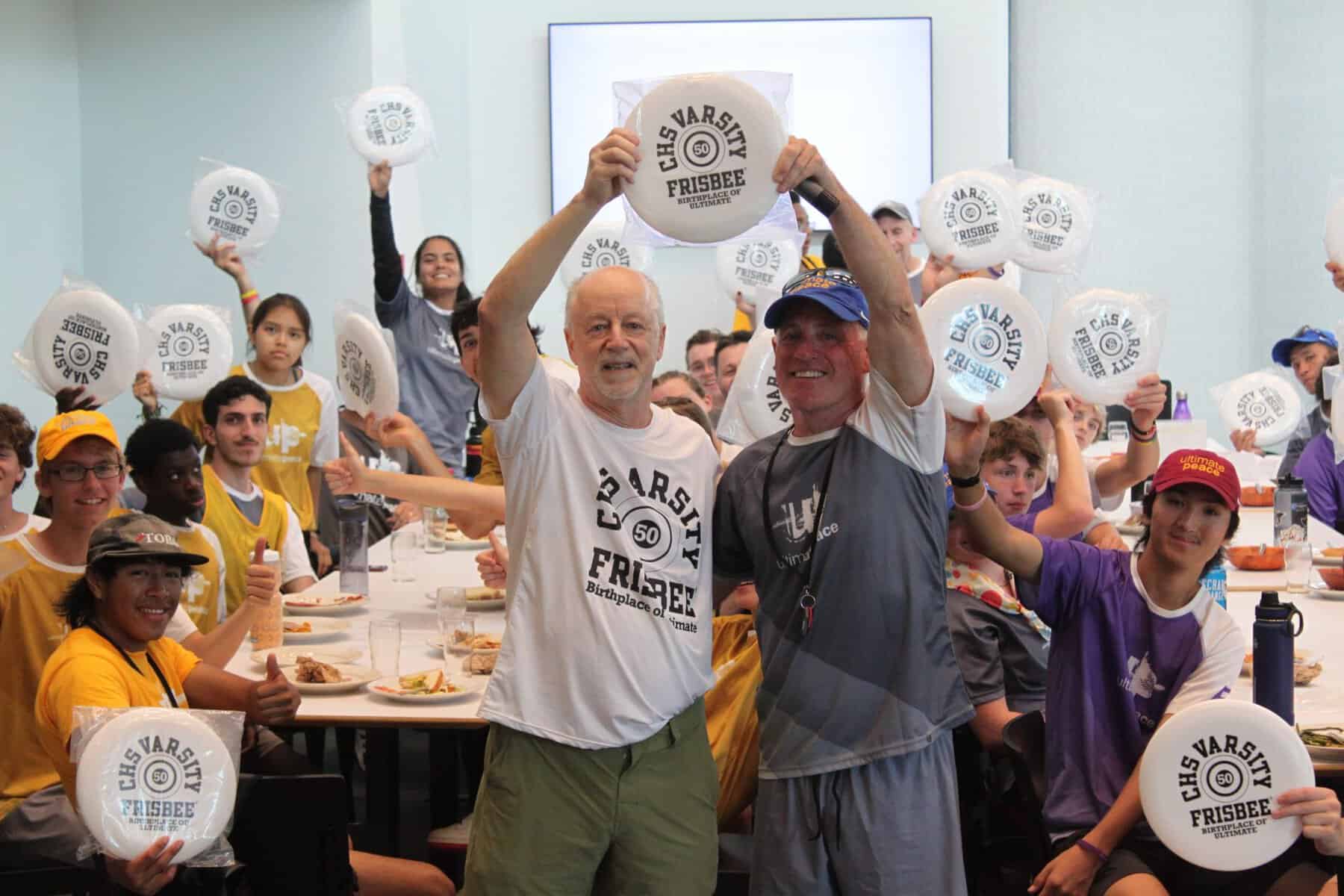

The game that became known as ultimate Frisbee – now known simply as ultimate – was first played as a semi-organized sport at Columbia High School in Maplewood (Essex County), said Lawrence Township resident Paul Schindel. He visited the camp and handed out souvenir Frisbees from the sport’s 50th anniversary in 2018.

Two Columbia High School students attended a camp in Massachusetts in 1968 and brought back an antecedent to Frisbee, Schindel said, adding the two students and another wrote the rules for the new game.

“From our start in Maplewood, the first three or four graduating classes from Columbia High School played at the varsity level,” Schindel said. “They were responsible for spreading it to over 50 college teams. The game has become global.”

An ultimate team consists of seven members who fling the Frisbee disc into the air toward their teammates to catch. The objective is to reach the goal line and score points, Barkan explained.

Ultimate is similar to football, lacrosse, basketball, ice hockey and other team sports, but with one exception, Barkan noted.

“There are rules, but no referees to make a call if there is a disagreement on the playing field,” he said. “Instead, it is left up to the players to work things out. Settling issues on the field is key to the program and its success.

“They learn to resolve issues on the field. If there is a disagreement on the field, they resolve it on the field. It translates into how to live off the field. Players carry those lessons and values into the workplace.”

Equally important is what is known as the Spirit of the Game, Barkan said. He described it as a set of principles that consist of equal parts – sportsmanship, camaraderie, a sense of fair play and cooperation among competitors.

“If you lose the respect of your opponent, then what have you really won?” he said, “even if you have more points.”

Barkan said he was introduced to ultimate in summer camp in the Poconos as a teenager. He enjoyed the sport and continued to play it into adulthood.

Barkan played on teams that competed in seven national ultimate and two world ultimate Frisbee championship tournaments. He was also inducted into the Ultimate Hall of Fame in 2010.

While those accomplishments are notable, that’s not what drives him.

What drives him, Barkan said, is bringing together young people who would never have met off the playing field – especially Israeli, Arab and Palestinian youths in the Middle East.

Barkan founded the Ultimate Peace program in 2008 to build bridges between the disparate communities. He had lived in Israel for one year as a young child while his father taught at a university. He lived in Israel later, as an adult.

“I was aware of the division, the inequities and the violence in the Middle East,” he said. “It bothered me. As a Jewish man, I felt like I had to do something.

“I felt like the potential was there to use (ultimate Frisbee) to bring young people together who would never have met. They are told in school to hate each other.”

The game is a safe way to have fun without thinking bad thoughts, to be teammates and to see what happens, Barkan said. It builds relationships outside of the program and opens doors.

“I wanted to do this (Ultimate Peace camp) in the United States. We are not at war, but there is divisiveness and violence. We need to help youths see each other (as friends),” he said.

Barkan saw himself transformed by the game. When he played, he had to self-referee. He had to grow up. The players answer to themselves and to the community, he said.

Ultimate Peace campers Javier McGinnis and Gio Gerber and Javier McGinnis said they have learned how to communicate with others. Gerber has been playing the sport since he was a young child, while McGinnis is new to it.

McGinnis has been playing for about 18 months. He lives in Atlanta, Ga. He is home-schooled, but joined the Maynard H. Jackson High School ultimate team.

“I like the community and the spirit of it,” McGinnis said. “It taught me to be a better leader and to work with different people and situations on and off the field.”

Gerber, who is a junior at Columbia High School in Maplewood, learned about ultimate when he was in first grade. He became involved in the sport in middle school and has continued to play in high school.

“It taught me how to communicate with people and how to solve a dispute in a calm manner,” he said. “Those are skills you have to master.”

Gerber said there is more of a sense of family on an ultimate team than on other sports teams. He said he trusts everyone that he plays with, and it is something that is unique about ultimate.