By JENNIFER AMATO

Staff Writer

SOUTH BRUNSWICK — On Nov. 25, 2012, then-Private First Class Chris Molnar was visiting his two friends before they went back to college after Thanksgiving break.

Molnar had just been granted a 10-day leave of absence after completing three months of boot camp training at the United States Marine Corps on Parris Island, South Carolina, on Nov. 12.

“All of a sudden, my vision went sideways; it went blurry and I couldn’t focus,” the lifelong Kendall Park resident said.

He tried to blink and focus on his phone, not suspecting that as a 19-year-old that this was anything of concern. However, once the right side of his face began to droop and his right arm would not work, his friend’s mother called the paramedics. With slurred speech and nonsensical conversations, he was temporarily given water and M&Ms out of the assumption he was suffering from low blood sugar.

However, once the EMTs from Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital in New Brunswick arrived, questions abounded about drug use.

“A young person my age — the first thing they assume is drugs,” Molnar said.

He thinks he may have been administered Narcan for a suspected heroin overdose, because his body’s behavior was so out of character.

“I was having a stroke,” Molnar explained. “But the first thing they think of is drug overdose.”

Molnar said he remembers being in and out of consciousness and some fleeting moments of clarity once admitted to the hospital.

He said his brain scan showed a stroke caused by a blood clot. A super high-dose blood thinner was given to Molnar to dissolve the clot, and his stroke ended later that night, he recalled. He said he still had double vision, he could not talk and suffered from “a hell of a headache.” His right arm still would not move.

When his heartbeat registered questionably to doctors, they discovered he had heart failure and an enlarged heart.

And he was told he needed a heart transplant.

“I was kind of in denial. I just graduated boot camp. How could I be in heart failure?” he said.

Unbeknownst to him, doctors told his parents that if he was not transferred to a pediatric hospital, he was going to die. They told family members that Molnar was not going to make it through the day.

Molnar said that shortly after that conversation, a bed had opened up at the Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center. Because it would take too long to send a transport team from New York, an ambulance from Robert Wood took him directly into Manhattan.

He said while traveling, he kept passing out and his blood pressure was bottoming out.

Once he arrived at Columbia, further testing revealed a more dire prognosis — he was in end-stage heart failure, and his heart was five times the normal size. His heart was only pumping out 13 percent of the blood needed for his organs, so his heart grew in size to compensate, he said. The rest of the blood pooled and clotted, breaking off and causing the stroke. His left lung partially collapsed because his heart was so large, and other organs were affected.

Perplexed enough that he had had one stroke, doctors said that scarring on his brain showed the November incident was his second stroke. Between the second and third month of boot camp, Molnar had recalled a slight vision issue, which doctors determined to be his first mini stroke.

“I brushed it off as, I’m tired, I’m dehydrated, I’m exhausted, no big deal,” he said.

The medical staff tracked his heart failure and first stroke to the end of his first month at the Marine Corps. He was diagnosed with pneumonia at the time due to fluid in his lungs, and a chest X-ray showed a normal heart. They believe that was actually the beginning of the heart failure.

He then suffered a third mini stroke on Nov. 30 while in the ICU.

Later diagnosed as idiopathic cardiomyopathy, Molnar said basically “they had no freakin’ idea why I went into heart failure.”

There were no viral, bacterial or foreign items in his system, and he has no family history of heart problems. He said doctors described it is a crash-and-burn-type situation.

On Dec. 3, 2012, Molnar underwent his first open heart surgery to implant a left ventricular assist device to keep him alive while he waited for a heart. He was an in-patient until Dec. 22, and for one month lived at home on a heart pump. He returned to the hospital once or twice a week for checkups.

But by mid-January 2013, however, Molnar’s heart pump developed blood clots inside so Molnar had to spend the next month in the hospital on an IV that would keep his blood thin.

During this time, he had a “false alarm” for a transplant. He said he was being wheeled into surgery when doctors said the heart they had prepared for him had died upon retrieval.

Eventually being dismissed from the hospital, Molnar went home and started physical therapy. He said he often thought about the pump malfunctioning overnight, causing him to die in his sleep.

“I basically was just numb to everything,” he said. “I was prepared to start my Marine Corps career and all of a sudden I’m in-patient in a hospital with machines keeping me alive,” he said.

Finally, on April 9, 2013, Molnar received his heart transplant — though not without complications. His liver and kidney were damaged, he had a high fever and he had blood clots throughout his upper body. He spent another two weeks recuperating in the hospital.

However, Molnar maintains a very positive attitude.

“The heart is doing great,” he said. “It’s all mental. You’re your biggest motivator. You have to keep that inside you and know you’re going to survive.”

He did have one minor rejection where his body attacked the new heart as a foreign object, so he is on immune-suppression medication for the rest of his life. However, his prognosis is positive, only having to monitor a small clot in his right shoulder. The heart should be good for around 20 years. He has some residual chest pain and scar tissue, even these years later. He is cleared to work out and do daily activities; he must avoid grapefruits and pomegranates due to interaction with medication; and he cannot eat raw meat.

“In the grand scheme, I can’t complain,” he said. “It’s my ‘new normal.’”

He said he does not know much about his donor, other than the person having the same blood type and a similar height, weight and age. He said he knows the heart was flown in from somewhere.

He said that transplant patients are allowed to wait one year after surgery to contact the donor’s family to allow time for grieving. He has not received a response yet to his letter.

“I’d like to meet them,” he said. “How do you put into words that I’m alive because your husband, your mother, your father, your brother died? … What do you say other than ‘thank you’ times a trillion?”

Still considered a Marine, Molnar spent one year rehabilitating at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Maryland with the Wounded Warrior Battalion. He said being around other veterans helped him cope.

“It was not a regular Marine Corps experience, but enough of an experience that it helped close out that chapter of my life somewhat at least,” he said.

On April 30, 2015, Molnar medically retired from the United States Marine Corps as a lance corporal and started attending Mercer County Community College that fall, with the goal of achieving a communications degree in order to pursue a career in public and motivational speaking.

“I want to start my career and make a name for myself,” he said.

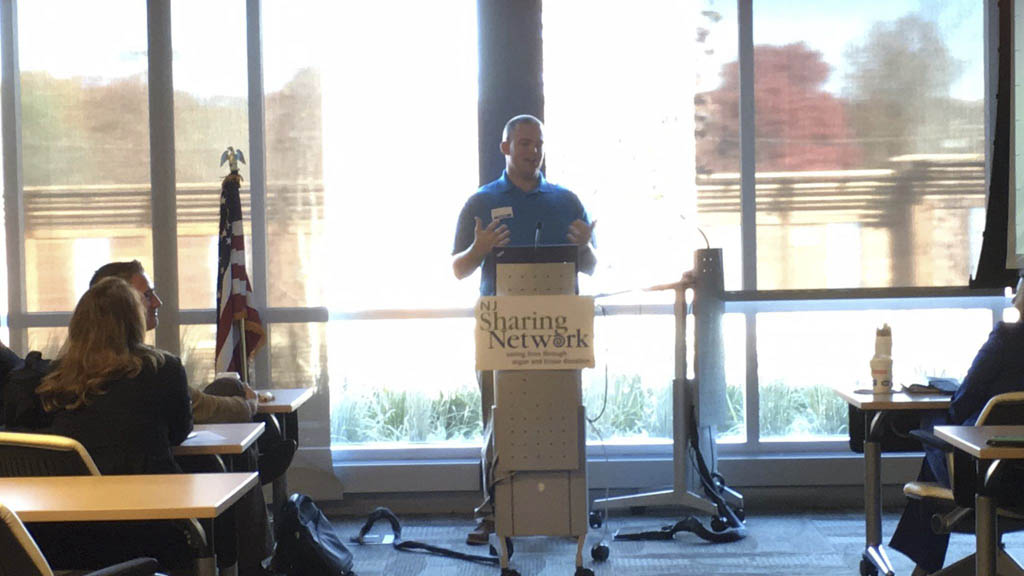

He currently volunteers with the NJ Sharing Network and Live On New York. He spoke on Nov. 10, the Marine Corps’ birthday, for the NJ Sharing Network and on Veterans Day, Nov. 11, at Mercer County Community College.

He also had his story featured on the television show “NY Med.”

“I love it. I’m writing a book on everything I went through. I’m trying to volunteer as much as I can,” he said. “I want to bridge the gap between being in the military and organ donation.”

Although his dream of serving in the Marines since the fourth grade was cut short, the few months he spent at boot camp helped him grow up quickly and readied him to face his struggles. As one of only three Marines who has had a transplant while serving in the Marines, Molnar is trying to boost organ donation registration in the veteran community. He has earmarked his life for helping other veterans, other people going through transplants, and especially veterans needing organ donation.

“There’s no guarantee your organs go to another veteran, but it’s a possibility,” he said, motivating vets to help each other out.

For more information on Molnar, visit www.Facebook.com/ChrisMolnarSpeaks.

Contact Jennifer Amato at [email protected].