By Jimin Kang

Contributor

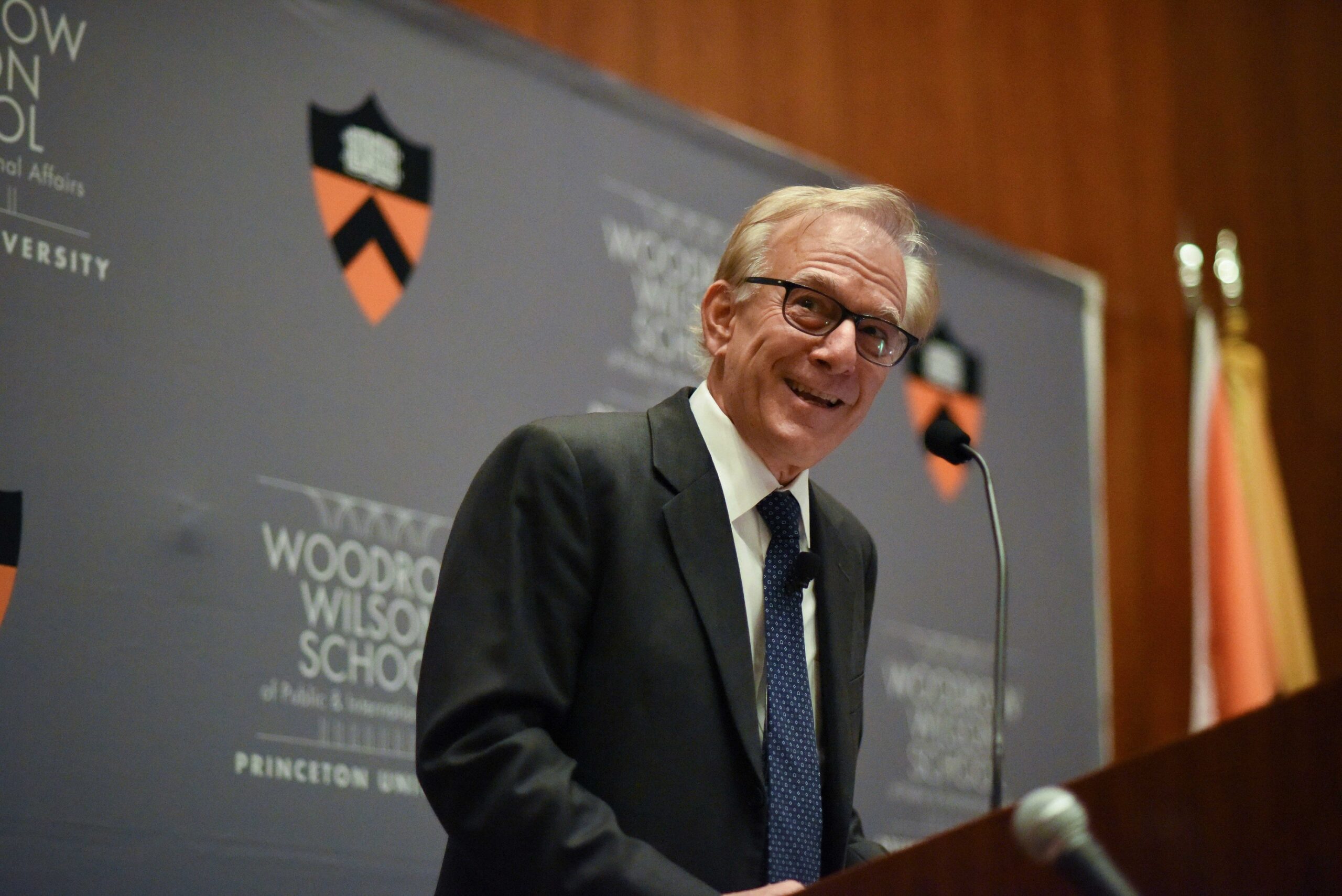

Political fragmentation in the United States is worrying to Washington Post foreign affairs columnist David Ignatius, who sees a growing similarity between the U.S. and the troubled countries he has observed during his journalistic career.

Ignatius, whose career has taken him around the world to cover various conflicts over the years, criticized President Donald Trump’s “destabilizing” foreign affairs policy and attacks on the press during a visit to Princeton University on Oct. 3.

“We’re fragmented to the point that we don’t even share facts in common,” Ignatius said to an audience of approximately 200 people. “That’s scary—we don’t have a factual base for making decisions. That’s something that I’ve seen in every country around the world that basically blew up.”

Having spent ten years writing for the Wall Street Journal prior to the Washington Post, Ignatius criticized Trump’s method of bringing North Korea to the table for denuclearization talks earlier this year.

Ignatius believes that despite the historic June 12 summit between Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-Un, changes on the Korean peninsula have been largely driven by Kim, who has been “determined” to “pivot towards economic development.” Though the president touted the meeting as a success, Ignatius believes the recent easing of tensions between South Korea and North Korea serves as an example of a “real denuclearization agreement.”

“The model of foreign policy success is what he did with North Korea,” he said. “You beat ‘em up, you insult them, you threaten to go to war with them… then, you know, you soften them up, then you make them do what you want.”

Aside from North Korea, Ignatius also pointed to trade-related tensions with Mexico, Canada and China, as well as U.S. involvement in Iran, Syria and Russia as actions that could drive wedges between the country and the rest of the world.

Looking back on his years of experience in foreign affairs journalism, Ignatius noted how things have changed since he first started.

After the Wall Street Journal assigned Ignatius to cover the Middle East in 1980, he went to Beirut to cover the Lebanese Civil War, where he experienced “a kind of journalism that, sadly, is disappearing.”

“That was a period in which journalists had a kind of invisible white flag,” Ignatius said, referring to his reporting in the 1980s. “Everybody felt that they needed us, or wanted us, to tell their story. One thing that has happened in our modern world is that people don’t need the Wall Street Journal, the Associated Press, to tell their message—they can use the internet.”

“Look at ISIS. ISIS communicates with its followers directly. It doesn’t need the intermediation,” he continued, referring to the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, a militant jihadist group that gained global prominence in 2014.

During this change, Ignatius started doing a different kind of storytelling: fiction. Ignatius has written ten novels in the spy genre, which were largely inspired by his experiences writing about the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) back at the Wall Street Journal. His latest book, “The Quantum Spy,” was published in 2017.

“Fiction is a look at the facts that interest me as a reporter,” he said. “Truth is complicated. In a novel you can let things be as complicated as they really are, and let the characters tell all the different sides of the story.”

For the most part, however, Ignatius sticks to journalistic reporting, which he has come to “love.”

“Every day journalists do things that make a difference,” he said. And if journalists want to continue making a difference in the current political climate, he believes, they need to not be “crazy” and “partisan.”

“We need to make sure that we really are balanced. We need to learn how to listen to people and then report it.”