EAST BRUNSWICK – During World War II, Seymour Nussenbaum, 95, had to use inflatable tanks, scripted radio broadcasts and other tools of deception in order to survive.

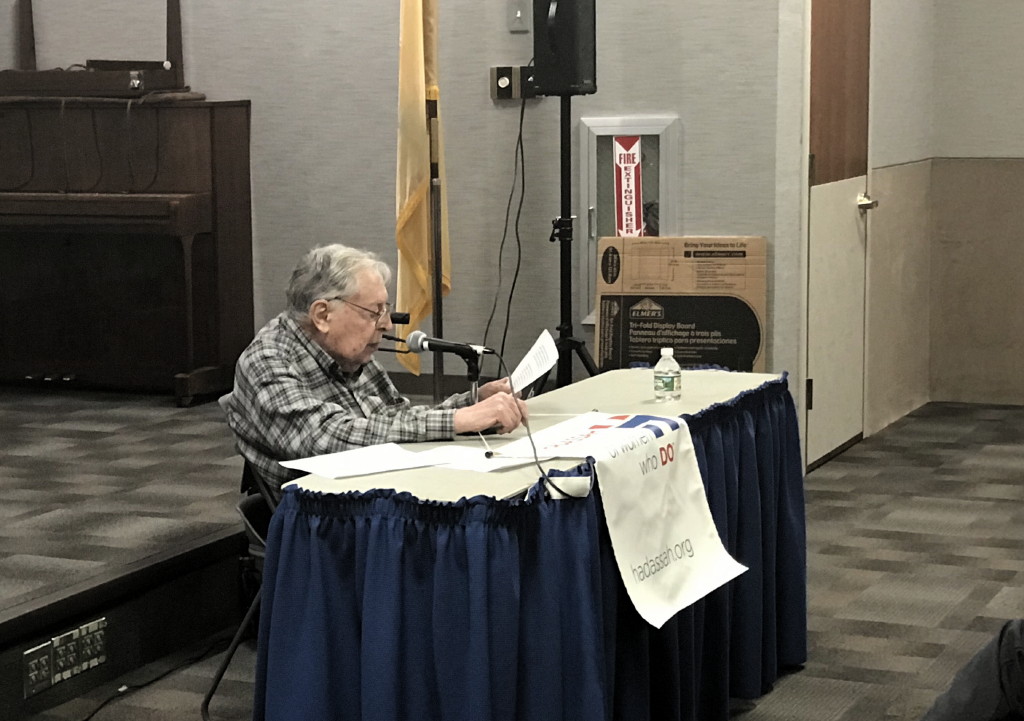

On Oct. 18, he spoke about his service in “The Ghost Army,” which is featured in a PBS documentary, in front of dozens of residents at the East Brunswick Library.

The event was co-sponsored by the East Brunswick Hadassah.

The Ghost Army was officially known as the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops. From June 1944 to March 1945, the unit staged 20 battlefield deceptions, beginning in Normandy, France. The deceivers employed an array of inflatable tanks, trucks, Jeeps and airplanes; sound trucks; phony radio transmissions; and even play acting to fool the enemy, according to a statement provided by the library.

East Brunswick Hadassah member Beth Hoffman said that a book about the Ghost Army is currently being made into a feature film in Hollywood by actor Bradley Cooper. There is also a bill pending in Congress to award members of the unit a Congressional medal.

Inspired by British deception efforts, Capt. Ralph Ingersoll, who was a well-known journalist before the war, suggested the U.S. Army create a phantom unit designed to fool the enemy right on the front lines.

Before World War II began, the Army was looking for professionals in the art world and recruited set designers, actors and artists.

Nussenbaum, who was born in Manhattan, was brought up in The Bronx where he attended Herman Rider Junior High School and DeWitt Clinton High School.

After graduating from DeWitt Clinton High School in 1939, his family moved to Brooklyn, where he attended night classes at the Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music and Art and Performing Arts and Pratt Institute, according to Hoffman.

Registering for the draft in December of 1942, Nussenbaum said he was in his first year of college at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn when he registered.

“Knowing that I would be going into the service, I took a course in camouflage offered by the Army at Pratt. I was inducted into the Army in February of 1943 and sent to Virginia for basic training. … On March 23, 1943, I was sent to Fort George G. Meade in Maryland to finish my basic training and begin advance courses in camouflage,” Nussenbaum said. “We trained there until January of 1944. … Once there we were informed about our mission. We were told we were concerned counterintelligence and our mission was deception.”

The Ghost Army was composed of 1,100 men who used visual, sonic and radio deception to deceive the German Army.

To carry out visual deceptions, the Ghost Army had a camouflage battalion composed of 350 men, who were mostly artists. Members of the visual battalion were tasked with creating camouflage to protect an Army plant in Baltimore where B-26 bombers were made against German air attacks.

Nussenbaum served in the Army from February 1943 to November 1945 and was mainly attached to the 603rd Engineer Camouflage Battalion, according to Hoffman.

In Europe, members of the camouflage battalion would use inflatable soldiers, tanks and Jeeps to deceive German soldiers.

“Our first dummies were made of wood and burlap. Rubber dummies came later as the wood and burlap were to hard to handle. We trained in the use and repair of the rubber dummies … in preparation for overseas service,” Nussenbaum said. “On May 2, 1944, we boarded the ship at the New York Harbor and landed in England after a rough trip. Immediately, we begin to prepare for our part in the invasion of France. We sailed from England on July 18, 1944, and arrived off of Omaha Beach in Normandy, France, after a stormy voyage, riding out the storm off the coast of France for six days.”

Using sound to fool the German Army was a new idea in World War II. The Ghost Army would use pre-recorded sounds of moving trucks, tanks and other activity, which were played over 500-pound speakers with a range of 15 miles.

By some estimates, German Army units would gather as much as 75 percent of their intelligence through radio intercepts. In response, more than 100 skilled radio operators from the Ghost Army would impersonate Army transmissions to trick the German Army.

“On Jan. 14, we set our headquarters in … France and as soon as the Germans were defended in that sector we began to move into Germany. We had various missions, some of which I went on,” Nussenbaum said. “Since I was attached to headquarters company I stayed behind on many of the missions to service the men in the field; [however,] I did go on a few missions to the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany.”

With many of the soldiers in the Ghost Army being artists, they would sketch and paint their fellow unit members, people and places they encountered while serving in Europe. After the war, some of the members of the Ghost Army became famous, including fashion designer Bill Blass, painter Ellsworth Kelly and photographer Art Kane.

While serving in the Ghost Army, Nussenbaum said he would sketch constantly and would send a lot of souvenirs home. He said once he married his wife Vera Nussenbaum, who was a Holocaust survivor, he put away the souvenirs he collected from the war.

After being discharged from the service, he returned to Pratt Institute and graduated in 1948 with a degree in illustration. Nussenbaum found work as a package designer responsible for both structural and graphic aspects of the package. He worked for a folding carton establishment for 32 years, eventually becoming the art director. When he left that job he freelanced and took other jobs within the industry. Nussenbaum did his last freelance job in 1997, according to Hoffman.

Nussenbaum said the Ghost Army and its wartime missions remained classified for decades and members were told not to discuss what they did with their loved ones. Today, he is on the advisory board of the Ghost Army Legacy Project and resides in Monroe Township.

“I didn’t tell them anything. I made up a scrapbook when I came out of the service. I wanted to go back to college and I had for months to wait until the new semester started so I had sent home a lot of junk and I went through it and made up scrapbooks. I never mentioned in the scrapbooks what we did,” Nussenbaum said.

After the screening and discussion of the documentary, residents were able to view some of Nussenbaum’s artwork he created while serving in the Ghost Army.

For more information, visit www.ghostarmylegacyproject.org.

Contact Vashti Harris at [email protected].