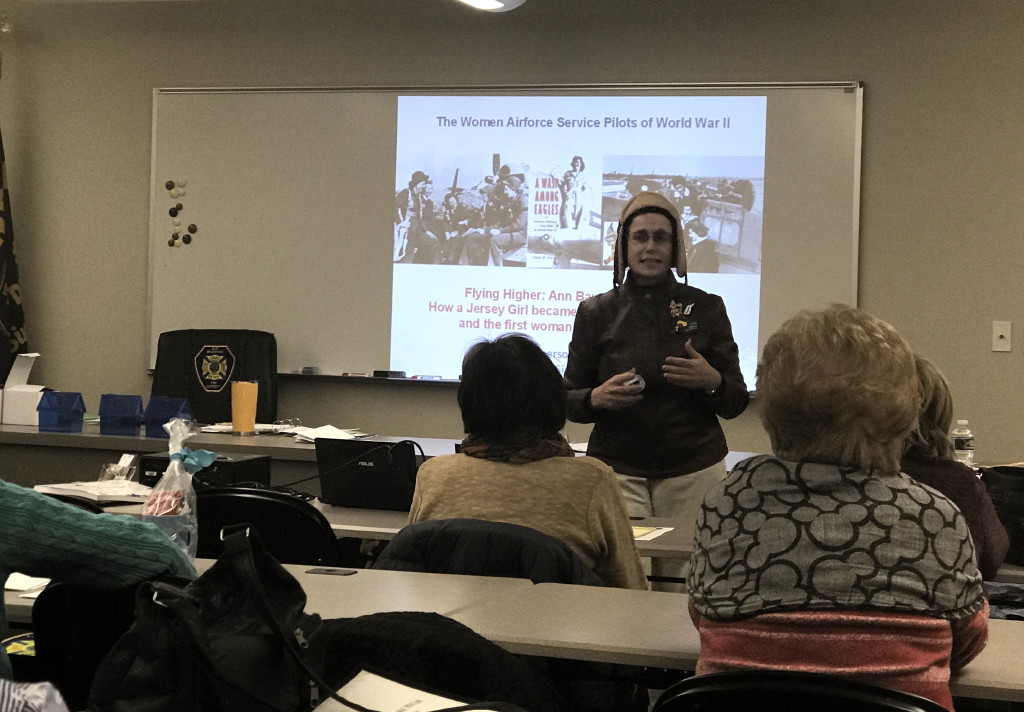

EAST BRUNSWICK – Impersonating World War II American aviator Ann Baumgartner is no small feat.

To tell the story of the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP), living history presenter Carol Levin told dozens of residents at an East Brunswick Women’s Club meeting on Nov. 13 that the all-female flying force flew more than 60 million miles in 78 different kinds of aircraft during World War II.

Baumgartner was born on Aug. 27, 1918, in Georgia, but grew up in Plainfield.

“The notion even of flying military aircraft was a pretty new idea if you [can] imagine. It had only been 15 years since the Wright brothers had done their 59-second flight on the windy hills at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, to aircraft being used in a military fashion,” Levin said.

Recognizing their daughter’s book smarts, Levin said Baumgartner’s parents paid for her to attend Smith College to major in chemistry in 1935.

After graduating, Levin said Baumgartner’s first job was as a correspondent for the New York Times, writing a question-and-answer column for the newspaper, while also working as a lab technician in a vitamin lab in Newark.

In the summer of 1941, Levin said Baumgartner went to Somerset Hills Airport to inquire about taking flying lessons and ultimately completed the 35 required hours needed to get her pilot license. She said Baumgartner also paid $500-$700 to get her pilot license, which was six to eight months of an average woman’s salary at the time.

On Dec. 7, 1941, Japanese planes attacked the United States Naval Base at Pearl Harbor. On Sept. 4, 1942, Levin said Baumgartner read in the morning newspaper the “My Day” written by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who wrote that women pilots are weapons ready and needed to be used.

Levin said that cosmetics business owner and pilot Jacqueline Cochran helped establish the WASPs, but started as an accomplished beautician at Saks Fifth Ave in New York City.

Along with a number of other flyers, including her friend Amelia Earhart, Levin said Cochran helped spearheaded the campaign that women should be allowed to serve as pilots in the Air Force.

“Then we had Pearl Harbor and what the women were saying becomes abundantly clear very quickly,” Levin said. “If you think about the fact that Pearl Harbor happened in December 1941, we had 19,000 airplanes built … and what the women were saying was evident because those airplanes were staying on the tarmac.”

Levin said by Sept. 10, 1942, it was announced that the military would establish the WASPs, which was the first group of female military pilots. She said Gen. Henry Arnold put Cochran in charge of the WASP training program, which was called the Women Flying Training Detachment; however, neither program had military status so they were given civilian status.

Levin said 25,000 women applied to be in the program and at the time, all applicants had to already have their pilot’s license to qualify – though most women did not even have a driver’s license.

Accepted into the program, Levin said Baumgartner reported to Houston Airport in mid-January 1943 and instead of finding military barracks she arrived at a dusty disused airfield.

“They had put the program in the part of the Houston Airport that wasn’t being used and they were boarding us in rat-infested motels and we were having ineligible food at diners and so forth and would go back and forth to the airport each day,” Levin said. “To add insult to injury, the men trainees who were living in barracks with all expenses paid were getting $250 a month. Women who had to pay for the rat-infested motels … got $150 a month.”

Levin said the women were given uniforms in men’s sizes, forcing them to tuck, fold and sew their uniforms to modify them to their sizes.

“Despite all of these drawbacks we were getting to fly and we were getting to fly with other women,” Levin said. “For many of them, they had been the only girl interested in aviation in their own airfield.”

Levin said the program was also terrifying, rigorous and fast-paced.

“We knew that their male instructors were looking for any excuse to get rid of us. They wanted to prove that men are better than women,” Levin said.

Once the program was transferred from Houston to Avenger Field in Sweetwater, Texas, Levin said the women needed 200 flight hours to graduate from the program. She said women flew in three levels of airplanes and did 400 hours of ground school which included physics, navigation, flight theory, meteorology, aircraft engines that included putting them together and taking them apart, radio, and Morse Code.

The last test before graduation was a night instrument flight where two girls and an instructor would have to fly at night, according to Levin.

When two WASPs along with their instructor died after taking their night flight test, Levin said, “That’s when we learned the reality of what not being military meant. Because we were not military the family could not display a Gold Star in their window to recognize their lost daughter. There were no flags for the coffins and there was no military insurance. A male trainee would have gotten $10,000. … The military did not even provide money to send the remains home if the girl did not have money in her account [so] we passed the hat to send her home.”

Levin said 11 WASPs died in training and 27 WASPs died in service.

Baumgartner graduated on Sept. 11, 1943, and went on to test American, Japanese and German airplanes for the U.S. Air Force, according to Levin.

In October 1944, WASPs were informed that its division would be disbanded due to the bill that would have militarized the WASPs being denied, according to Levin.

After flying her last plane, Levin said Baumgartner married flight engineer Bill Carl and had two children. Baumgartner would go on to teach airplane pilots, write for science publications and wrote her memoir about her life as a WASP in 1999.

“As for our service, it was deliberately erased, it was marked confidential and was kept away from researchers and the public for 35 years. … By 1972, we had the 30th reunion and the following year we heard that the Air Force was accepting their first class of women pilots,” Levin said. “Even the Air Force had forgotten about us, so the women set about restoring our name in the record. Sen. Barry Goldwater tried to have the militarization amended for us; it failed.”

In 1977, the WASPs were finally given military status after months of lobbying, and several years later were given medals. Today, their uniforms are in an exhibit at the Smithsonian Museum, according to Levin.

A plaque honoring the 38 WASPS who died was installed at the Air Force Academy in 2000. The National WASPs Museum was established in 2005 in Sweetwater. In 2009, former President Barack Obama signed a bill given all WASPs the Congressional Medal of Honor.

For more information about the East Brunswick Women’s Club, visit www.eastbrunswick.org/content/198/221/401.aspx.

Contact Vashti Harris at [email protected].