The dawn of Aug. 15, 1945, in the Pacific was no more important to me than any other except that it became one of the happiest days of my life. It was the day Japan surrendered and I realized there would be life for me after World War II.

I wasn’t counting on much of a future until then but, along with thousands of others expected to die in the impending invasion, I would return home and finish college, start a career, find my wife and raise our children.

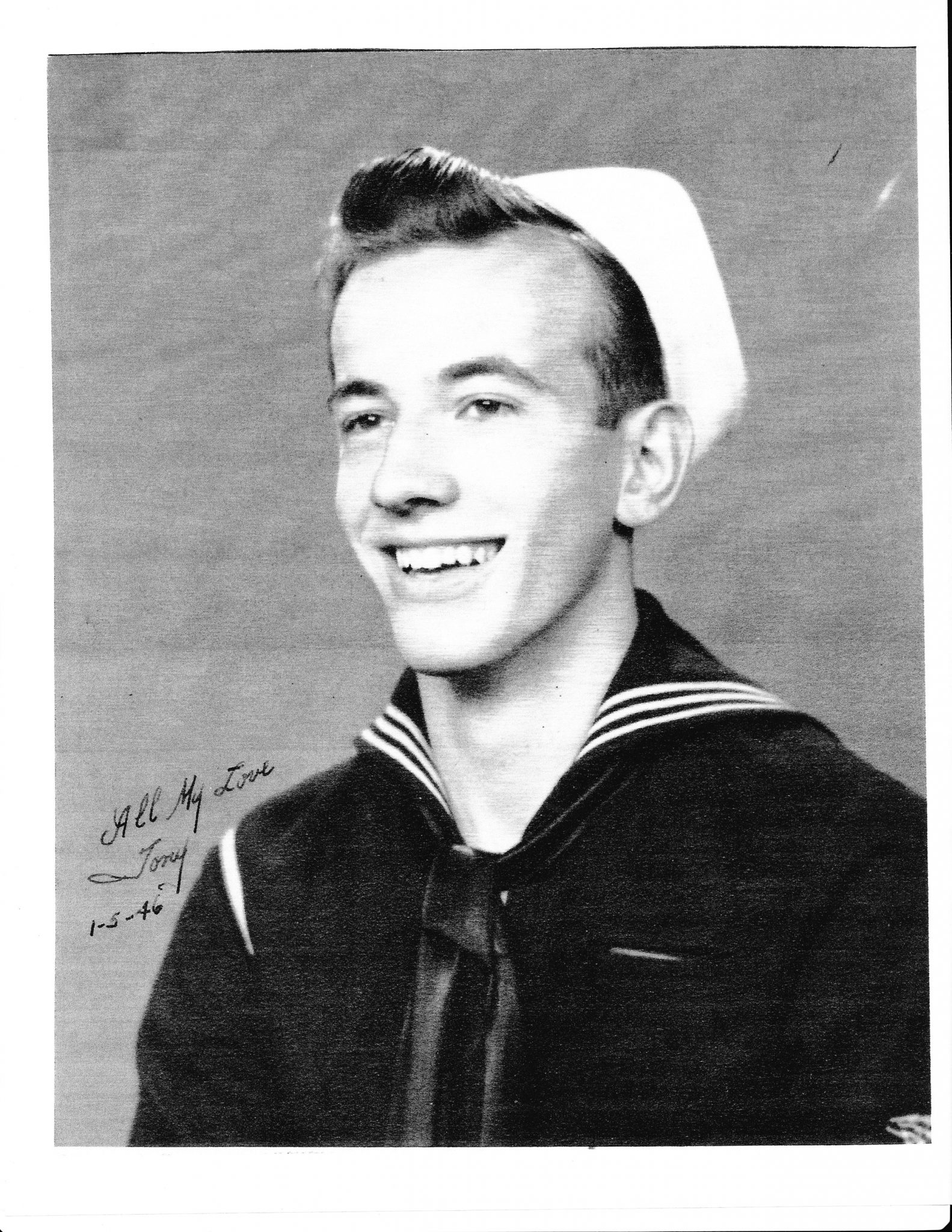

But right now I was a 19-year-old petty officer-radarman aboard the USS Amsterdam, a Cleveland class cruiser with 1,300 sailors and Marines protecting Admiral Nimitz’s and Admiral Bull Halsey’s Third Fleet aircraft carriers and battleships.

We were a Naval bombardment and carrier strike force that pounded Japan’s military installations for three months in preparation of the invasion by American and allied forces. We didn’t know it then but America was planning to invade the Japanese homeland within 90 days in an air, sea and ground attack that would cost hundreds of thousands more lives.

We knew that the Japanese were planning to go all out with artillery, bombs, rockets and Kamikaze suicide planes This was to be the greatest invasion since D-Day at Normandy, but few of us talked about it.

We had doubts about our survival and thought if we didn’t talk about it, it might go away. On Aug. 6 our ship’s radio blared that the United States had dropped an atomic bomb, whatever that was, on Hiroshima. It helped explain the huge explosion we had just heard, the sudden morning darkness that enveloped us and the 8-foot waves rocking us.

Ship-to-ship communications confirmed that none of our warships had struck a mine or were under attack. This had to be a bomb, we thought, so powerful that we were feeling and hearing it from offshore nearly 90 miles away.

We had unleashed the power of the sun, as it was described, on the land of the rising sun, which flattened the entire city and obliterated 80,000 people.

Three days later a second atomic bomb vaporized Nagasaki with nearly the same number of deaths, and newscasters began speculating a quick end of this war. But we had learned to ignore such rumors. Just another bigger bomb we thought. But at 8:15 a.m. on Aug. 15 everything changed.

More than 500 carrier planes of our task group minutes away from wreaking havoc on Tokyo, Kure, Kobe and Osaka were suddenly recalled. The ship’s public address system barked that the war was over, that Japan had surrendered.

One pilot radioed “no hits, no runs, no errors.” All of the strike force jettisoned their bombs 45 miles offshore and then returned to wild celebrations. Up went our battle flag while sailors and Marines pounded each other in joy and fired their guns. The fact that we would survive was almost beyond belief for those of us living with so much anxiety and fear. But our euphoria didn’t last long.

Even though the Japanese government had officially surrendered, the sky was soon darkening with Japanese suicide planes whose pilots were hell bent on reaching their heaven. They pounded us with guns blazing and bombs exploding into our ships or the sea.

Sailors were kissing girls in Times Square but we were still fighting for our lives in a war that the Japanese had lost – a fact that their Kamikazes refused to accept. For the next two weeks our fleet dodged and weaved as our 40- and 20-millimeter guns responded with devastating effects on incoming Kamikazes. But the fleet’s deep-freeze food storage compartments were filling up with the dead who hours before were celebrating their survival.

Then finally, the suicide planes that weren’t already splashed by our firepower flew off to a more peaceful, fuel-less ending in the sea or to the disgrace of a landing unharmed.

We sailed into Tokyo Bay, where in less than 20 minutes, General Douglas MacArthur and Japanese authorities ended a war that lasted four years. After walking the streets of burning Tokyo, we boarded our ship and headed for Okinawa to pick up wounded and dead Marines and moved them to Astoria, Oregon, which threw a festive welcome to the first warship to return home to the United States.

Some have criticized our use of atomic bombs to end the war. But while saddened by the terrible toll of deaths, both sides agreed their use actually spared as many as a million more lives.

Anthony Galli lives in Pennington. He has authored four books, including two on the Civil War exploits of his great-grandfather with his Fourth Pennsylvania Cavalry in Virginia and Gettysburg. He has worked for UPI, TIME magazine and Sports Illustrated with hundreds of his bylined articles appearing in magazines and newspapers across the country. He is a U.S. Navy veteran of World War II.