Blacks have made some strides in overcoming racism since the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s, but more needs to be done to bridge the gap and to achieve full societal equity and equality.

That’s the assessment of four panelists who spoke at a roundtable discussion on how to make New Jersey an equitable place to live, vote and thrive, sponsored by the Lawrence Township chapter of the League of Women Voters.

Assemblywoman Verlina Reynolds-Jackson (D-Mercer/Hunterdon), along with Lawrence Township’s Black Solidarity Group co-founders Kyla Allen, Jayda Parker and Kayla Phillips, offered their views at the April 7 virtual forum. The three co-founders are members of Lawrence High School’s Class of 2015.

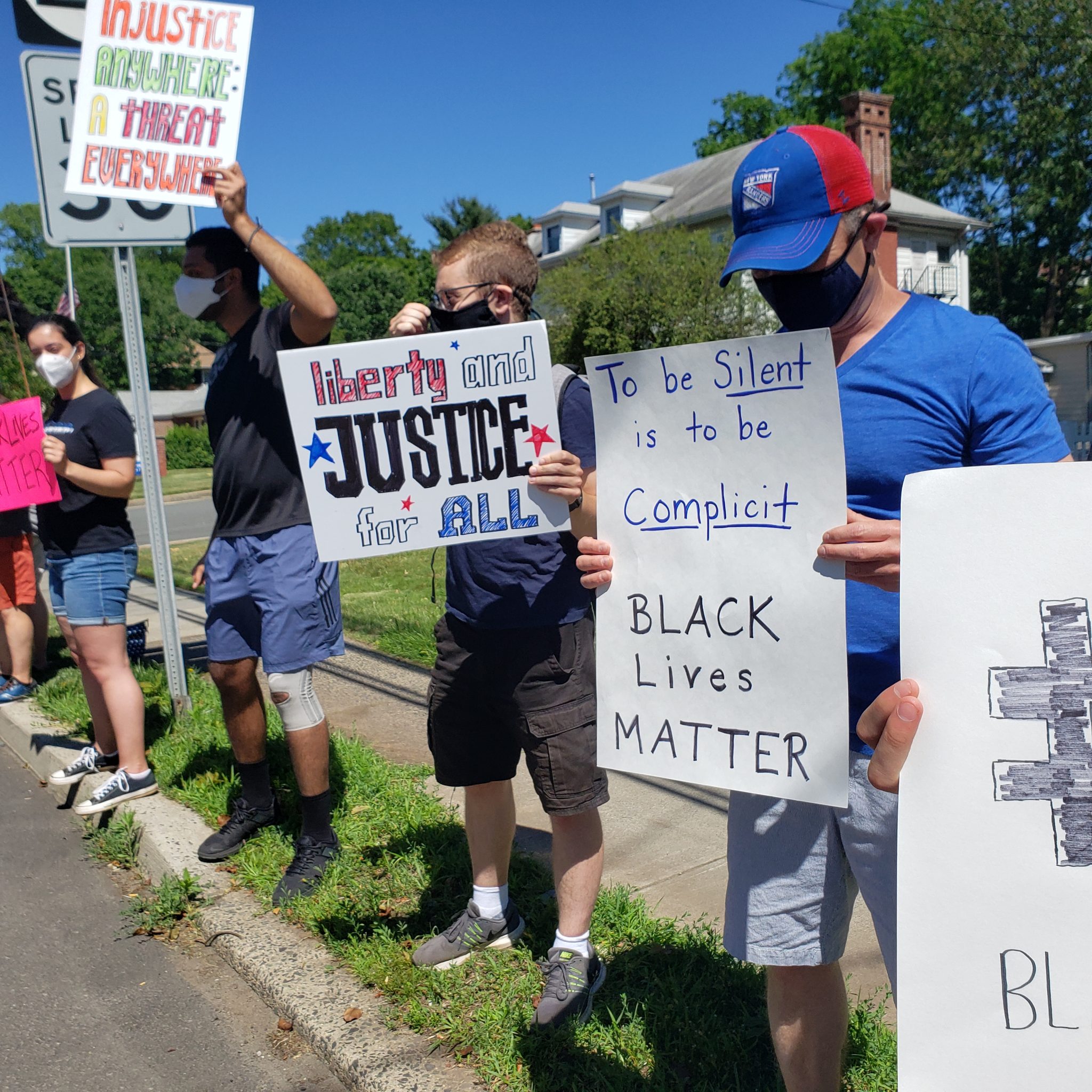

The wide-ranging forum touched on racism, police brutality, violence and racial injustices, as well as the significance of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Asked how to reduce police brutality and violence in Black and Brown communities, Parker said police officers need to be held accountable for their actions. The patrolman needs to be accountable to the sergeant, who needs to be accountable to the lieutenant, up the chain of command.

“I think the problem with the police is that racism is deeply rooted,” Parker said.

Police officers are accustomed to handling situations in a certain way – especially older police officers, she said.

Allen, Parker and Reynolds-Jackson agreed that change must start with police department training. New police recruits, as well as police leadership, need to take implicit bias training, Reynolds-Jackson said.

Allen said the training course to become a cosmetologist is longer than the police academy courses that train new police officers. She asked rhetorically, how is a police officer going to enforce the law if he or she does not know the law? Police officers should have to earn a degree in criminal justice, she said.

Reynolds-Jackson said lawmakers have been discussing the possibility of requiring police officers to be licensed, just as attorneys and health care professionals are licensed by the state. The police have the ability to take a life, she said.

The State Attorney General’s Office also has issued a new set of directives that will keep track of an officer’s use of force, which can weed out officers who are prone to using excessive force, Reynolds-Jackson said. Police officers have an obligation to intervene when they see another officer using excessive force, she said.

Defunding the police also was raised during the forum. Allen, Parker and Phillips said that it’s not taking away money and police cars from police departments; it’s about reallocating some of those resources. The term “defunding the police” is often misunderstood, Parker said.

While ” ‘defund the police’ is an overall national call,” Allen said, it comes down to reviewing each community and its police department because the needs are different in each town. The resources for the police department in some towns might be “perfectly allocated,” but in other towns, there is no reason why so much money has been budgeted for it, she said.

Phillips said she is “in the middle” on defunding the police. There is no need for the police to have military-style equipment. On the other hand, if a police officer with a “racist” mindset only has a baton and handcuffs, “they will find a way to hurt you,” she said.

Allen, Parker and Phillips said that despite Mercer County’s diverse population, it does not make the county or its residents immune to racism.

“Just because Mercer County is diverse, that doesn’t mean it’s not like anyplace else. It doesn’t mean there isn’t racism. Growing up, you knew which town had a certain reputation – which town not to drive through at night,” said Allen, who lives in Lawrence.

Phillips, who now lives in Trenton, said she is surrounded by Black and Brown communities, so she does not have the direct contact with racism that she might experience if she lived in Hopewell, Lawrence or Ewing townships.

“I might be comfortable walking to the store with my neighbors (in Trenton), but when a policeman pulls up, I am terrified for my life. I believe there is racism in government and the police,” Phillips said.

Parker, who now lives in Princeton, said racism is a “plethora” of things. She said she thought there would be less racism at Lawrence High School because of the diversity of the student body, but she discovered that it was not true.

“You might think somebody might be your ally because their skin color is close to yours,” Parker said. But deep down, that person might not be an ally. Sometimes, it’s about that would-be ally trying to fit in with the right group and not wanting to be friends, she said.

“From my experience at Lawrence High School, the things I dealt with were things that you would have thought I would have dealt with in the South years ago,” Parker said.

On the Black Lives Matter slogan and movement, Reynolds-Jackson said it matters to her because it is an effort to acknowledge Blacks as human beings. It’s about education, jobs, housing, food insecurity and health disparities. Blacks have been marginalized, she said.

“What we are saying is that we are human beings, too. We want to be represented in this country as an equal to everyone else. We want to have some of the rewards and benefits that everybody else has. We have to continue to advocate for ourselves,” she said.

But Allen, Parker and Phillips did say Black Lives Matter has become commercialized. Black Lives Matter started in the aftermath of the death of Trayvon Martin in 2012, Parker said. It did not start after the deaths of several Blacks at the hands of police in 2020.

Black Lives Matter has become “trendy” and people are using it too freely, Parker and Phillips said. It needs to mean something more, Parker said. People say it, but they don’t understand it.

“Saying it is obvious,” Allen said. “Our lives matter. Of course, all lives matter, but all lives are not being harmed and killed and being taken away from families at the hands of law enforcement. That’s the purpose of Black Lives Matter.”

Phillips said it is easy for companies to put Black Lives Matter on a T-shirt, or on Tiktok or Instagram. People “put it out there, and they think that’s all there is, just to say it in solidarity.” But its meaning is deeper than that – it’s about mental health, education and health care, she said.

Wrapping up the discussion, Reynolds-Jackson recalled the words of diversity consultant Verna Myers: “Diversity is being invited to the party. Inclusion is being asked to dance.”