By Huck Fairman

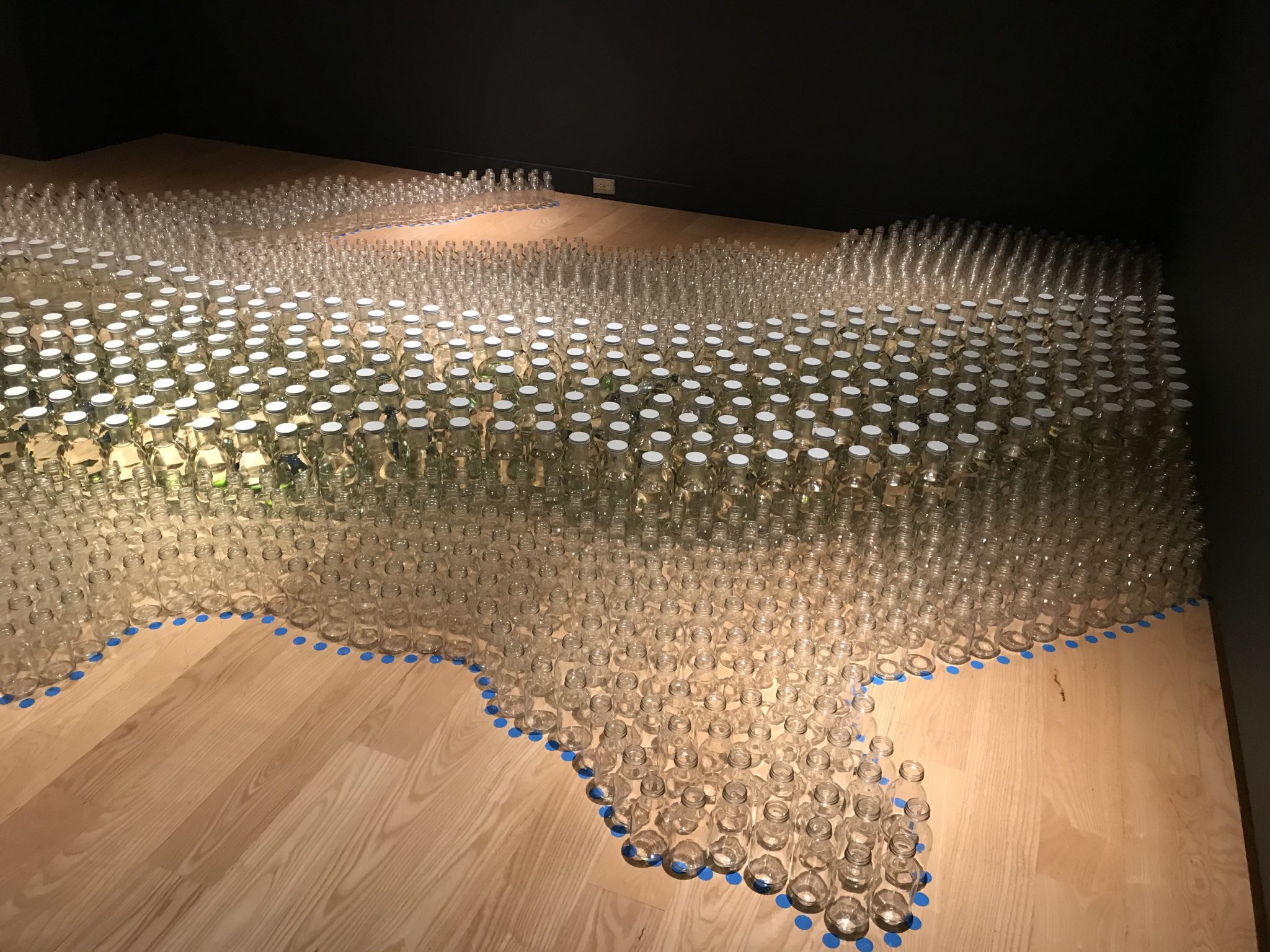

Our country has not been particularly effective in its recycling programs. A recent NPR article provided an overview of where we are. Only 30-35% of all materials are recycled. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimated that only 8.5% of plastics refuse is recovered to produce new products. Where is the rest going? Into our environments.

Fortunately, a number of states are taking action, transferring the responsibility from consumers to manufacturers. In the past 12 months, legislatures in Maine, Oregon and Colorado have passed “extended producer responsibility” laws on packaging. The legislation essentially forces producers of consumer goods — such as beverage-makers, shampoo companies and food corporations — to pay for the disposal of the packages and containers their products come in. The process is intended to nudge manufacturers to use more easily recyclable materials, compostable packaging, or less packaging.

Now, the New York legislature is deliberating on two extended producer responsibility bills as its session nears its June 2 close. Lobbying by business and environmental groups has been particularly intense around details such as what recycling goals must be met and who sets them. Industry and environmentalists alike believe that when a state as big as New York adopts a law, it creates a template or standard that other states might adopt too.

Extended producer responsibility — a concept that came from two Swedish academics, Thomas Lindhqvist and Karl Lidgren in 1990 — took root in Europe 30 years ago. Many U.S. states have such policies for e-waste and mattresses. But their adoption for packaging is fairly recent in the U.S., and those programs won’t be fully up and running for years.

While each state’s legislation varies, the system generally works like this:

• Beverage companies, shampoo-makers, food manufacturers and other producers will keep track of how much of each sort of packaging they use.

• These producers will reimburse government recycling programs for handling the waste, either directly or through a consortium called a “producer responsibility organization.”

• Fees will be lower for companies that use easily recyclable, compostable or even reusable packaging, a mechanism that supporters say will provide incentives to adopt more sustainable practices.

• Recycling centers will use the money to cover their operating costs, expand outreach and education, and invest in new equipment.

“We think corporations will produce less virgin materials because they are charged by the amount they put out there, and certainly less eco-unfriendly materials,” said New York state Sen. Todd Kaminsky, a Democrat from Long Island who sponsored one of the bills pending in Albany.

To consumers, the recycling system would pretty much stay the same. But the packaging around consumer products would likely look different. If the incentives work, there will be less packaging overall, and whatever packaging that would be used would be made more often of compostable or easily recyclable materials, such as glass or aluminum.

The burden of recycling has fallen not just on consumers to sort their containers properly, but also on cities and counties, where officials once thought recycling could pay for itself. But that has not been the case, especially because of recent decisions by China and other Asian countries to refuse to accept plastic waste imports. In 2021, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) calculated that the management of plastic waste costs about $32 billion per year.

Extended producer responsibility will hopefully be a step forward in addressing this global problem. As many have read, plastics in water bodies are proving fatal to many species and are not healthy to humans. The efforts to improve recycling are not merely addressing aesthetic blighting but the health of human communities.